|

Displaying items by tag: Art Market Analysis

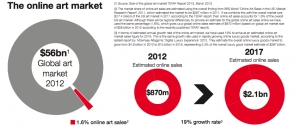

The Online Art Trade Report by the British insurance group Hiscox estimated the value of global online art sales at $1.6 billion in 2013, up from $870 million in 2012. The report’s findings are based on a survey of 506 international art buyers, collectors, and galleries from a database belonging to ArtTactic, an organization that specializes in art market research and analysis. The study estimated that the online art market will grow to $3.8 billion by 2018.

According to the report, 71% of art collectors surveyed have purchased artwork without seeing it in person first and 89% of the galleries surveyed claimed that they regularly sell to clients using a digital image only. Nearly 25% of 20- to 30-year-olds surveyed said that they had purchased art online and nearly half of the collectors over 65-years-old surveyed said that they had bought art directly online.

Robert Read, Hiscox Global Head, Fine Art, said, “This research distills the views of collectors, galleries and the greater art community and it tells us that trading online is now an established and accepted way to buy and sell art. Increasing accessibility can only be a good thing, and we are seeing new players coming into the market from a range of territories, at all ages and price points, which is an exciting – if somewhat unexpected – development."

According to the report, online art sales account for 2.4% of the estimated value of the global art market, which in 2013 was $65 billion.

Click here for the full report.

The most striking thing about the art market—especially as it has grown from the small, passionate community of the early 1990s to a $50bn industry today—is that it largely functions along self-regulating lines. Prices, authenticity, standards and practices are all arrived at among the art world itself, without much reference or recourse to government—it feels like a libertarian’s dream of a free and unfettered market. But, the recent scandal engulfing the 165-year-old Knoedler Gallery, with the authenticity of works attributed to US painters including Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollock coming under scrutiny (The Art Newspaper, January 2012, pp4,5), suggests that more adult supervision is required.

“Over the years, we have hoped that there would be some sort of investigation” into the circulation of allegedly fake works, said Richard Grant, the executive director of the Diebenkorn Foundation in an interview with the New York Times last December. A federal investigation has now been launched into the alleged forgeries, but questions over market regulation have dogged the industry for years. William Cohan, a New York Times writer, published a scathing attack on the trade in August 2010. “The art market is utterly unregulated. There are few rules, other than the basic ones of commerce and ethics. There is no Federal Reserve Board or Securities and Exchange Commission,” he wrote, referring to issues surrounding bronzes cast from rediscovered plaster moulds that were sold as genuine works by Degas (The Art Newspaper, May 2010, p7).

Cohan’s proposed solution was not to create an agency to govern the art market but to shoehorn the trade under the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. However, Cohan made no effort to show how the oversight might work.

Indeed, there would be practical problems with art market regulation: works of art are not fungible, and value is impossible to calculate against any independent measure. Moreover, it is not the lack of laws that bedevils the art market but a see-no-evil, ask-no-questions attitude among many in the trade. It is worth bearing in mind that aggressive attributions, fudged provenance and too-good-to-be-true discoveries are nothing new. For more than 25 years, beginning in 1912, the American art historian Bernard Berenson helped the English art dealer Joseph Duveen to sell masterpieces to US plutocrats, famously embellishing attribution on occasion to justify the price.

Middlemen

Since then, however, the market has grown exponentially, which means that there are more people involved. For example, in the recent case brought against Knoedler and its former director Ann Freedman by the London-based collector Pierre Lagrange last December over an allegedly fake $17m Pollock, the number of intermediaries only added to the confusion. At least four individual entities stood between the seller and buyer: the dealers Jaime Frankfurt and Timothy Taylor acted as unwitting agents and liaised with Knoedler gallery and its then director, Freedman, on Lagrange’s behalf. The gallery and Freedman in turn dealt with Long Island art dealer Glafira Rosales, who was herself allegedly representing the mysterious Mexican seller.

Responsibility

While intermediaries are not necessarily a sign of trouble, the chain of people involved in the Lagrange case seems to have created a diffusion of responsibility. The situation is not atypical. “There used to be clear pipelines that art would go into, but now there is a complex matrix,” says David Houston, the director of the curatorial department at the Crystal Bridges Museum. The institution has made no secret of its desire to buy a major Pollock, but is navigating busy waters. “We see a lot more middlemen in the market today than we did ten years ago—people who are part-adviser, part-dealer and part-picker,” he says.

Nevertheless, many in the trade say that Pollock’s massive prices (notably Mural, 1943, which is owned by the University of Iowa Museum of Art and is valued at $140m), and the fact that his output was limited, mean that the whereabouts of his works are relatively well known. Any buyer seriously looking for a work at the highest price level should “know exactly which works are out there, who owns them and whether they’re ready to part with them”, says the art adviser Todd Levin of the Levin Art Group.

The Asian art auctions in New York this autumn produced a number of predictable results. Once again, the Chinese works of art that appeal to Asian buyers and notably mainland ones, did best. As always, works from collections did well. Christie’s continued to outperform Sotheby’s, by a large margin. Other sectors, such as Japanese and South Asian art, remained patchy.

What also emerged, and is probably a worrying aspect for the auction houses, is the apparent failure of the “premium lots” system at Sotheby’s. Bidders on these high-priced lots (over $500,000 in the US, over $1m in Hong Kong) are only allowed to go for them after registering their interest in advance and paying a deposit. They can’t bid online. The reason? There have been a number of cases of Chinese buyers defaulting on auction purchases, and Sotheby’s inaugurated this system in Hong Kong in 2007—before the aborted sale of two bronze Zodiac heads at Christie’s Yves St Laurent sale in Paris in 2009.

This autumn, Sotheby’s New York’s auction of Chinese works of art on 14 September included five “premium lots”; four failed. Only a Northern Wei votive stele found a buyer at just over $1m (est $500,000-$800,000), going to Eskenazi. But the stars of the sale, two archaic bronzes (one estimated at $2.5m-$3m) and two pairs of 17th-century Huanghuali chairs (estimated at up to $1.5m) were bought in.

It looked like a rerun of April’s Meiyintang sale in Hong Kong, when Sotheby’s designated 22 of the 77 lots as “premium”, but half of them, including the two most important pieces, were bought in (both subsequently found the same private buyer).

The auction Artists for Haiti, organised by New York’s David Zwirner gallery and Christie’s, takes place on 22 September. It is perhaps the most ambitious charity event since Sotheby’s 2008 auction for the rock star Bono’s Red charity, which finances Aids, tuberculosis and malaria programmes in Africa. The Haiti sale includes high-value, new work by artists such as Luc Tuymans and Jeff Koons.

There are similarities between the two events: Red’s $42.6m total—the result of a perfect confluence of strong market, blue-chip artists, and a celebrity-driven cause—wouldn’t have been possible if Damien Hirst, after a meeting with Bono, hadn’t approached artists including Banksy, Jasper Johns and Julian Schnabel. In Artists for Haiti’s case, Zwirner, after a trip to Haiti with the actor Ben Stiller who works with charities in the region, also opened up his contacts book.

While not all charity auctions are on the scale of Artists for Haiti or of Christie’s forthcoming Japan relief sale with Takashi Murakami (date yet to be confirmed), the dealers give up their time and the auctioneers conduct them, gratis. While the likes of Christie’s and David Zwirner become involved in charity auctions out of corporate responsibility, there are some additional fringe benefits. Such events are good for public relations and can help in winning business: existing and potential clients are often involved in charitable organisations. And they are a good deal for collectors too. Although New York State requires sales tax, there is no buyer’s premium. One exception was the Red sale, for which there was some financial incentive for Sotheby’s, which took a 10% buyer’s commission (below its usual 12% to 25% rate, but a fee nonetheless). Collectors who donate a work get a tax deduction on its full market value; buyers get one on the difference between the retail value of a piece and what was paid above it.

Charity auctions have been around for a while. Sotheby’s decorative arts specialist Robert Woolley, who died in 1996, became a star charity auctioneer in the 1980s and 1990s. Lydia Fenet at Christie’s says there was a huge increase in charity auctions in the boom years between 2000 and 2008. Then, hedge fund money made for more visible events, such as the star-studded Robin Hood Foundation Gala, but these suffered during the downturn. Recently fundraising events have increased again, despite the still flailing economy.

They differ from normal public auctions. Alcohol is served, buoying moods. Auctioneers are not obliged to abide by the regulations (and the New York State laws) that govern regular auctions, including following specific bidding increments, so have more sway for drawing out bids.

This can influence the market. It’s unusual that artist records are set, but after the Red sale, there were 17, including Banksy at $1.9m and Howard Hodgkin at $792,000 (both still the artists’ auction records). Because it was at Sotheby’s, these results are listed on Artnet (most charity auctions are not) where there is no obvious sign it was a charity auction. This is misleading: who knows if these prices would have been achieved in a standard public auction?

Benefit sales are not always ideal for dealers or artists, however. A common refrain among dealers is that there are too many of these events, packed with too much low-value art. (Zwirner is keeping Artists for Haiti to a modest 26 lots of expensive, mainly primary market work.) Some institutions’ boards do not come out in support, leading to lacklustre results. Dealers and artists do not want to turn anyone down—dealers are swayed by collectors who are trustees at institutions; artists feel indebted to spaces that helped their careers. Neither do they want to donate second-rate pieces, since influential people will see these flop. Still, there are complaints about second-tier “benefit art”; some artists get asked so often that they’ve made large edition pieces for donations. In June, Mat Gleason, an art critic for the Huffington Post, advised artists: “Don’t ever donate your art to a charity auction again.” Artists who donate receive a tax deduction only on the cost of materials. And dealers want to control markets, making any auction problematic.

|

|

|

|

|