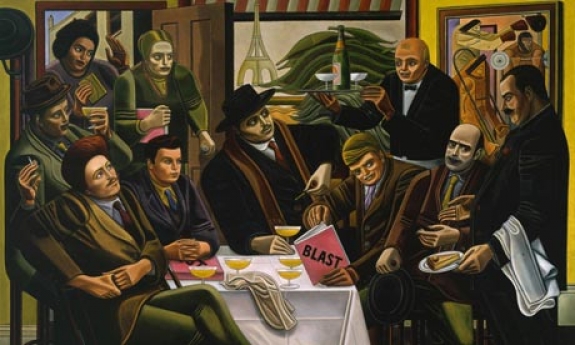

The Vorticists, the summer exhibition at Tate Britain, opens next month: I saw the show in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation. Who were the Vorticists? Galvanic Ezra Pound was the band's vocalist, belting it out. With his ziggurat hair, he was the impresario, the excitationist, the amplificationist, just as another writer, Marinetti, was the vocal focal point of the Italian Futurists. Every movement needs a writer to whip up the manifesto. The philosopher TE Hulme was its theorist. The leading participants were expatriates – the American sculptor Jacob Epstein, the ex-Canadian Wyndham Lewis, the Frenchman Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, the American photographer-in-exile Alvin Langdon Coburn.

The movement was short-lived, barely lasting from 1914 to 1917. Epstein was never an official Vorticist. Nor was David Bomberg. But both could see the commercial point of Vorticism – the biz of the buzz. And they made a more lasting impact than various other English painters who were drawn into the Vortex – Pound's wife Dorothy Shakespear, Jessica Dismorr, Frederick Etchells, Helen Saunders, Christopher Nevinson, the Yorkshireman Edward Wadsworth, William Roberts. Apart from Roberts (barely represented here), none of these slight painters is touched with talent: they are canon fodder. They are the infantry, the grunts, bulking agent, the barium meal which creates the sense of a movement. The flush New York lawyer, John Quinn, antisemite, lover of Lady Augusta Gregory, patron of TS Eliot and the avant-garde magazine the Dial, also threw money at and down the Vortex.

And what was Vorticism? For all its international recruits, it was a parochial British attempt to emulate and excel Cubism and Futurism. Another ism. No wonder (in 1925) Hans Arp and El Lissitzky co-authored the trilingual Kunstismen (Isms in Art in English). Constructivism was set up in Russia. Fernand Léger's Tubism was just round the corner. There was Suprematism, Expressionism, Verismus . . . Arp and Lissitzky don't mention Vorticism, however. Why not? Because it was effectively invisible, a variant, a hanger-on, a wannabe. Vorticism was keeping up with the Cubists. A great many of the catalogue essays here are intent on translating the art into ideology. Every picture is worth 1,000 words. Or more. And we get them. The art historians assiduously mine the art for traces of Bergson, Kant, Newton, Max Stirner, Nietzsche, Georges Sorel.

Actually, the impulse behind Vorticism, the theory, is simple. The machine is central to Vorticism. Everything was subsumed to the machine. Le Corbusier famously said in 1923 that a house was a machine for living in. By then, the idea was domesticated and cosy. In January 1914, Hulme wrote that "the specific differentiating quality of the new art [will be] the idea of machinery". It is an irony that Langdon Coburn's mechanical Vortographs – disappointing double- and triple-exposures – meant he was swiftly dumped by Pound. (Langdon Coburn's straight photograph portrait of Wyndham Lewis shows an inadvertent apostasy of vision: note the great gathering of cubist folds in Lewis's ample crotch.)

In Orlando, Virginia Woolf definitively mocked the idea that literature, that prose style, was the toy of social conditions: "Also that the streets were better drained and the houses better lit had its effect upon the style, it cannot be doubted." Apparently, Wyndham Lewis was of the opposite persuasion. Social conditioning was crucial: he is against prettiness, he favours abstraction, because "a man who passes his days amid the rigid lines of houses, a plague of cheap ornamentation, noisy street locomotion, the Bedlam of the press, will evidently possess a different habit of vision to a man living amongst the lines of a landscape". However, this glib assimilation of seeing to surroundings – falling for a formula – is effectively repudiated by Wyndham Lewis when he subsequently writes: "In a painting certain forms MUST be SO; in the same meticulous, profound manner that your pen or a book must lie on the table at a certain angle, your clothes at night be arranged in a set personal symmetry, certain birds be avoided, a set of railings tapped with your hand as you pass, without missing one." What does this mean? Lewis is invoking superstition and ritual – and the iron law of instinct.

Eliot means much the same thing when he writes, in After Strange Gods, that theories of romanticism and classicism – Eliot was a classicist – count for nothing at the moment of composition, when it is impossible "to repair the damage of a lifetime". You can read the sex manual but the warm living woman will come as a complete surprise. In art, the hand and the eye are decisive. The brain guides the eye which guides the hand. Or so we think. But frequently the chain of command is disrupted, reversed, and the mind sees what the hand has already done. We look for inevitability.

And, once or twice, we find it in this exhibition. Jacob Epstein's Rock Drill (1913-15) was reconstructed in polyester resin by Ken Cook and Ann Christopher in 1973-74. It is the exemplary Vorticist art work. It shows a man on a tripod who is one with his machine. His drill is also his rigid proboscis, his hard, angled phallus. The tripod has weights (embossed Colman Bros Ltd Camborne England) on each leg, just above midpoint – which look like enlarged joints, or a bee's pollen knee-pads (only available in black).

The rib cage of the figure is exactly like the twin cylinders on a motorbike. He is recognisably human, true, but the human body, with its curves and trim little bum, has been made-over to the angular machine: it is an armoured exoskeleton. The arms are like greaves. I thought of Seamus Heaney's description of a motorbike lying in flowers and grass like an unseated knight. And I thought too of "Not My Best Side", UA Fanthorpe's marvellous poem about Uccello's St George and the Dragon in the National Gallery. In it, Fanthorpe imagines the young girl being rather taken by the dragon's equipment, when suddenly, irritatingly, "this boy [St George] turned up, wearing machinery".

Rock Drill is a tour de force, of energy, a vibrant sculptural collage. The head is turned so we can ponder its long, insect profile. It is immensely alien and spooky, even after you realise it is a long welder's mask, untitled and initially unrecognisable, tilted but not revealing a face. There is no face. The mask is the face.

The other great work is the Frenchman Gaudier-Brzeska's Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound. No photographic reproduction prepares you for the scale of this piece. Or the satisfying solidity of the marble. In the Palazzo Guggenheim, the authorised copy was beautifully lit so the shadows were incised and the planes visible. The only thing that is Vorticist about the piece is Gaudier-Brzeska's direct carving, without prior clay models or plaster-of-Paris maquettes – an earnest of Vorticist energy, of vitalism.