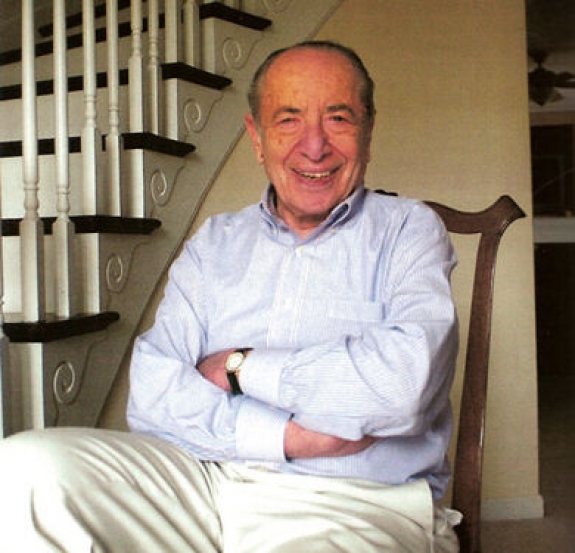

Courtesy of Margie Fishman, The News & Observer.

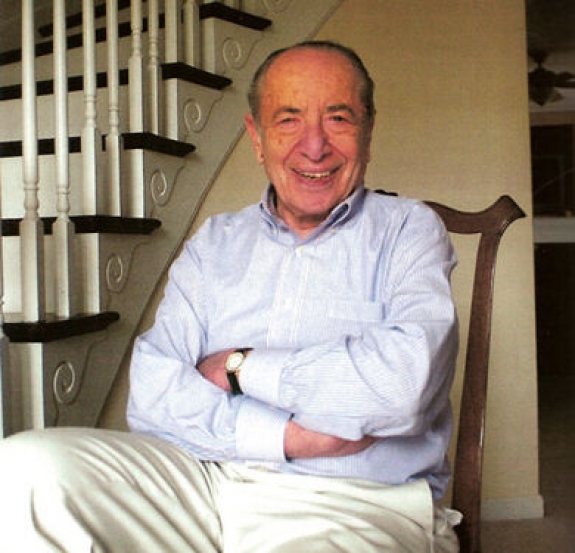

Courtesy of Margie Fishman, The News & Observer.

Many will be tempted to regard the passing of Albert Sack, who died on May 29 at 96, as the end of an era. He was the second of three brothers who perpetuated the legacy of their famous father, Israel Sack (1883-1959), continuing the family business for nearly 70 years until its doors closed in 2002.

Aside from Bernard Levy, who is 94 and in good health, Sack is the last of the great dealers in early American furniture who built major public and private collections in the middle decades of the 20th century. Along with the Levys, the Ginsburgs, John Walton, Joe Kindig, Jr. and a handful of others, Albert, Harold and Robert Sack were formidable tastemakers who shaped the content, interpretation and presentation of American decorative arts in museums across the country. With his “good, better, best” taxonomy, Albert Sack even devised a simple language for discussing the esoterica of furniture connoisseurship. The system was so seductive that it has been adapted for everything from office products to smart-phone apps.

Albert Sack represents the beginning of an era more than its end. A redoubtable Lithuanian immigrant who started the family firm in 1905, Israel Sack belonged to a pioneering generation of self-taught dealers in American antiques for whom knowledge was power. As underscored by surviving correspondence from the 1920s, Henry F. du Pont gravitated to the former cabinetmaker because he was a confident judge of quality, condition and authenticity.

Slight, nimble and impeccably groomed, Albert Sack in many ways resembled the courtly New York dealer Leo Castelli (1907-1999), a master merchant credited with elevating modern American painting and sculpture onto the international stage through a shrewd and much emulated combination of exclusivity and mass-marketing.

Like Castelli, Albert Sack harnessed the media for his own purposes. In a detail now largely forgotten, it was magazine editor Alice Winchester who urged Albert to expand an article that he had written for her into his first book, Fine Points of Furniture. Originally published in 1950, the best-seller was reprinted 24 times before Albert’s protégée, Atlanta dealer Deanne Levison, helped him write its sequel, The New Fine Points of Furniture. Published in 1993, the updated guide added “superior” and “masterpiece” categories to Albert’s original nomenclature. It is among these “masterpieces” that one finds some of the great objects that Albert Sack turned up during his many years on the road as the principal buyer for Israel Sack, Inc.

Though scholar-dealers are the norm these days in the nether reaches of the Americana trade, Israel Sack, Inc. was ahead of its time. The firm realized its mission of public education through its publication of the serialized volumes American Antiques from the Israel Sack Collection, through the brothers’ extensive schedule of lectures and appearances, and with glamorous, gallery-style installations. With these activities, Israel Sack, Inc. did much to professionalize an industry known more for its stubborn unconventionality than its sober business practices. A consummate showman, Albert Sack was at his best when he was sharing his wealth of knowledge with others. He is remembered for his generosity by the younger dealers, curators and auctioneers whom he mentored.

What has changed since Albert Sack first came of age is the pyramid structure of the antiques business, with its intricate wholesale alliances and network of smaller dealers feeding larger ones. Those relationships were disrupted by the ascendance of the international auction houses in the 1980s and later by digital technology.

Some things about Israel Sack, Inc. seem positively quaint. One is the father’s equation of formal beauty with patriotic virtue, a holdover from the day when objects were prized for their historical associations. The other is Albert Sack’s remarkable talent as a storyteller, a gift all but lost in the current generation. Again, digital technology may be partly to blame. As David Streitfeld recently wrote in the New York Times, “Words are not much valued on the Internet, perhaps because it features so many of them.”

For Albert Sack, who loved the chase and was always one breath away from his next discovery, the greatest objects were intimately associated with the people who made them and even more electrifyingly with those who had the passion to pursue them.

The world is far more ambiguous now. Where there were once old-time practitioners like Albert Sack there are now agents who move discreetly between the market and the academy, dealers who double as auctioneers, conservators who act as dealers and experts who are also television celebrities. It is in light of such complexity that the ordered world of Albert Sack, with its clear distinctions between better and best, most resonates.

Write to Laura Beach at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..