William S. Schwartz: Romantic Modernist

William Samuel Schwartz (1896–1977) was quite a character. His quirky handlebar mustache and voluptuous head of hair matched his quick wit, multilingual tongue, and penchant for opera. Schwartz’s oeuvre included landscapes, portraits, and still lifes. His imagination often penetrated the brush and large, yet controlled, canvases of abstracted driftwood, biomorphic forms, and allegorical narratives became commonplace. Despite his jovial personality, conflicting themes often revealed themselves in his work. Drawing from the fauve spirit and utilizing elements of cubism, constructivism, and surrealism, Schwartz considered himself a “romantic modernist,” refusing to bend to the whims of what was in vogue: “No one has told me I must depict this or that I must not venture upon that. I have painted in faith and in freedom—faith that somehow what I have done will reflect the best that is in me—freedom to choose my own themes in my own way.” 1

As a child in Smorgon, Russia, his parents could only rarely afford to buy him crayons to illustrate his imaginative stories. At the age of eleven, he earned a full scholarship to the Vilna Art School, and around 1914, came to New York City, an experience he later described: “…I was utterly unprepared for my first impression of America. That impression, in one word, was power! The sheer physical bulk of New York engulfed me.” 2

After a short period in New York, Schwartz moved to Omaha, where he focused on reading and writing English, a task more difficult than he expected, having, he claimed, already mastered Italian, Polish, and Spanish at a young age. He also met his mentor, J. Laurie Wallace, a locally renowned portraitist and teacher at the Kellom School. In the portrait J. Laurie Wallace (Fig. 1), the sitter gives an inquisitive leer, suggestive of intrusion on his pupil’s artistic trajectory. Rough and ungainly, the spattering of texture eluded to a transitional phase from Schwartz’s departure of realism and heavy-handed paint application to a more unabashed, modern technique seen immediately upon his arrival in Chicago, a step taken on the recommendation of Wallace.

Moving to Chicago in 1915, Schwartz studied under impressionist painter Karl Buehr at the Art Institute of Chicago. Known for his traditional approach to painting, Buehr wrestled with Schwartz’s departure from academic norms and lean towards fauve using greens and blues in nude studies, allowing for the deviations due to his confidence in the pupil’s abilities. I Pagliacci (Fig. 2), the earliest known work in ink by Schwartz, is a stylized interpretation of the three-act opera by Ruggero Leoncavallo. While the faces in the tree allude to the suitors of the heroine, Nedda, the hidden imagery was a portent of things to come in Schwartz’s work. In 1917, he graduated from the Art Institute with honors, and remained in good standing with the Institute, having his first solo exhibit there in 1926, with two others to follow.

Around this period, Schwartz completed an endearing portrait of his mother (Fig. 3). Hardly the brazen palette he was chided for using in school, the softened burnish of her face contrasted with the painterly handling of the fabric and carpet around her. This type of delicate realism was reserved for few occasions and rarely seen after the 1920s.

To earn money, “Bill,“ as he was known to his friends in Chicago, tried his hand at multiple jobs. including waiting tables and ushering. In 1921, he began performing as a tenor at the Ascher Portage Park Theater and later the Bohemian Opera in such operas as Rigoletto and Il Travatore. At one after-concert party, Schwartz met Mona Turner, a married woman and mother of two. Their love affair was one of symbiotic dependence. He adored her and included her likeness in many of his works and she admired his tenacity and talent, becoming a champion of his work for a lifetime. They married in 1939. Traveling by car, Schwartz and Mona frequently zigzagged the country, visiting friends while Schwartz painted en plein air.

While heavily engaged in Chicago’s musical scene in the 1920s, Schwartz was also producing works of varied genres. His Midwestern roots proved evident in his renderings of lush greenery and hidden back roads, but with a near-abstraction that called attention to the style within the work more than the subject itself. Quaint landscapes and views of ramshackle towns were represented with an acutely stylized hand; thick outlines paired with thin, reductive shading and rigid forms replaced curvilinear ones. His canvases conveyed his outer persona: a stark brightness in tone coupled with an unabashed palette.

Schwartz had an overpowering desire to assimilate into an American mainstream ideal. Having come from Jewish roots, he spent little time seeking his religion in the new country. Instead, Schwartz looked to Catholic priests for conversation and advice, and in fact rendered his own likeness for many portraits and scenes of Christ. In his Jesus of Nazareth (Fig. 4), Schwarz tackled the subject fearlessly, clearly modeling the portrait on his own features, replicating his bushy mustache and chin-length mop of hair.

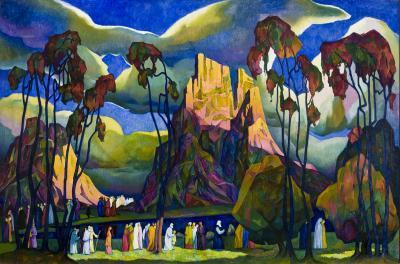

Schwartz’s personal journey was a continuing theme in his work. In The Pioneers (Fig. 5) of 1924, the ambitious canvas shows travelers crossing through a valley alongside a body of water. The light reflected on the mountains and forefront suggests the vast power of nature in contrast to the anonymous individuals. Although the work is definitive in its rendering of a sojourn, the scene is an elusive one offering little indication of the location, time, or ending point for the travelers — an introspective narrative for Schwartz.

In the mid-1920s, Schwartz started painting what many consider his greatest achievement, a surrealist series called the “Symphonic Forms.” While not documented, it was widely accepted that Schwartz attended Wassily Kandinsky’s solo retrospective at The Art Institute in Chicago in 1922.3 Similar to Schwartz, Kandinsky’s placement of symbols and lines was neither mistaken nor haphazard. Every facet of the multi-planed works demanded a response from the viewer. Marrying his two loves: music and art, the allegorical images became synonymous with one another as subjects. Elements in each canvas represent the notes, timbre, and visceral qualities music emoted. Cerulean blues are complemented with yellows and salmon hues in Symphonic of the Sea (Fig. 6), where mixed shapes bonded the composition into a mass of sea-like creatures and underwater life. Schwartz approaches Ballet of the Woods (Fig. 7) with the eye of a Cubist, using a palette of warm tones to represent the rigidity of the wood form protruding from varied planes that expand and undulate in all directions, emulating the organic tangles of nature. The placement, tone, and color convey a space that existed nowhere but in his mind. Citing a specific musical piece, Impassionata (or Appassionatta) (Fig. 8), represents Ludvig van Beethoven’s renowned piano sonata, sometimes referred to as Piano Sonata No. 23 in F minor. Full of pinks, reds, and oranges, the bright palette mimics Beethoven’s buzzing and frenzied arpeggios, particularly those in the closing of the third movement. Elements appear to sprout from the flat canvas as if spontaneous life sprang from the music itself. More monochromatic, Symphony in Driftwood (Fig. 9) depicts a controlled scene of imagined forms. Seemingly entangled, the organic growth appears to unravel before the viewer’s eyes, exactly as the artist intended.

- Fig. 11: William Samuel Schwartz (1896–1977)

Composers, 1934

Oil on canvas, 30 x 36 inches

Though the painting dates to 1934, a year before the establishment of the WPA, there is a WPA stamp on the reverse, suggesting the painting was entered as part of the relief measure after the work’s completion. Courtesy, Glencoe Public Library

In 1934, artist Ric Riccardo opened Riccardo’s Restaurant on vibrant Rush Street in Chicago. A painter and sculptor himself, Riccardo never allowed a fellow artist to starve and made certain his eatery and gallery were filled with personalities. It was here Schwartz shared drinks with fellow Art Institute graduates Anthony Angarola, Aaron Bohrod, and brothers Malvin and Ivan Albright, the latter known for their magic realism paintings. Schwartz later rented the studio above the restaurant, making his commute to the nightspot a happy necessity.4

Out of this camaraderie would result a work unlike any other, “The Seven Lively Artists.” Riccardo commissioned the work for the restaurant, and Schwarz collaborated with a number of his colleagues from the establishment along with other Chicago modernists.5 Schwartz contributed one of seven murals in the series, selecting music as his theme, a natural fit for the artist (Fig. 10). In his mural, eight feet high by four feet wide, a lone figure sits idly in an open field, dwarfed under a broad crimson sky: a melancholy and unexpected representation of melody, far removed from the earlier Symphonic of the Sea. The mural’s understated warm tones are at odds with Schwartz’s depiction of man against nature evoking a sense of longing to return to music, a profession he left and to which he never returned after his days in the Opera. The shared work on the murals marked a high point in the life of Riccardo’s artistic community.

Despite projects such as “The Seven Lively Artists,” Schwartz, like many fellow artists, was deprived of commissions during the economic hardship of the Depression (1929–1945). Marginalized more than ever, the creative class suffered detrimental losses in patronage. In 1935, the Federal Art Project under the New Deal Works Progress Administration Program provided a means for artists to create work documenting the social status of the country and its implications on future generations. Through the WPA, Schwarz received commissions to produce murals in post offices and public spaces. Surrounding this era, he created his “Americana Series,” a group of four paintings featuring poets, painters, composers and scientists. His Composers (Fig. 11) depicts four contemporary musicians, among them, Victor Herbert.6

The circa-1950 Self-Portrait (Fig. 12), which straddles the allegorical freedom of his previous works but includes hints of realism, is rooted in symbolism and Russian iconography. A sliver of Schwartz’s visage appears from behind a tall vertical column, one eye gazing upward. Frenzied, broken lines create floating forms in the upper-left quadrant contrasting with the tonal fleshy planes of his face. In the upper-right quadrant a mix of green and magenta reveals the suggestion of human forms with their backs facing outward. Theatrical lighting falls across the center of the canvas. The contrasting scratches, smooth passages, and shadows, while representing nothing that the viewer might recognize, seem to represent a formal organization of thoughts for the artist. The combination mimicked the elusiveness of the man many knew as a shameless self-promoter yet consummate friend, theatrical wonder, and pensive painter, emigrant turned American.

Schwartz continued to be a prolific painter throughout his life, cataloguing his works in a ledger and making frequent gifts of sentimental sketches to friends and family.7 Hardly considered avant-garde during his time, his symptomatic constructivist, surrealist and fauve works defaulted him to be a modernist, the label of which he falls under today. In later years he succumbed to Alzheimer’s disease and died in 1977. His legacy is the collection of works he left behind, housed in dozens of museums and collections internationally, an undeniably spirited and worldly view of his home and his heart.

-----

Yen Azzaro studied fine art at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received her BFA from School of Art & Design at the University of Michigan. She has been with Madron Gallery for the last five years and will leave her post as director in June 2011.

2. Ibid.

3. The first of two exhibits from the late Arthur Jerome Eddy Collection, September 19–October 22, 1922. The second exhibit took place December 22, 1931–January 17, 1932,

4. Riccardo’s Restaurant closed in 1992.

5. The seven WPA artists were Schwartz (Music), Malvin Albright (Sculpture), Ivan Alrbight (Drama), Aaron Bohrod (Architecture), Rudolph Weisenborn (Literature), Vincent D’Agostino (Painting), and Ric Riccardo (Dance). In 2002 Chicago philanthropist Seymour H. Persky acquired the murals for his personal collection.

6. The mural was discovered at Glencoe Public Library, IL, in 2007, and are as follows: Americana No. 1 Poets: Mark Twain, Walt Whitman and Edgar Allen Poe; Americana No. 2 Painters: Saint Gaudens, Bellows, Sargent, Innes, Whistler and Homer; Americana No. 3 Composers: Herbert, DeKoven, Chadwick, MacDowel; Americana No. 4 Scientists: Edison, Steinmetz, Bell, and Morse.

7. Schwartz’s personal ledger ends at #755 and includes paintings, prints, sculptures, and murals.