A Land of Liberty and Plenty Georgia Decorative Arts at MESDA by Daniel Kurt Ackermann

Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts

In 2009 the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) at Old Salem, North Carolina, more than doubled its collection of Georgia-made decorative arts. The museum celebrated this achievement with an exhibit entitled “A Land of Liberty and Plenty”: Georgia Decorative Arts 1733–1860.” Important objects from the pioneering Georgia decorative arts collection of Florence and Bill Griffin joined a small nucleus of objects acquired by MESDA’s founder Frank L. Horton over the museum’s first forty years. Several other objects were acquired as part of the museum’s ongoing effort to better represent the decorative arts of its seven constituent states: Georgia, Tennessee, Kentucky, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Together these Georgia objects—old friends and new acquisitions—tell the unique antebellum story of a place where the “Old South” of the Atlantic Coast meets the “Deep South” of the Gulf of Mexico.

|

Georgia Decorative Arts at MESDA

by Daniel Kurt Ackermann

In 1733 James Edward Oglethorpe (1696–1785) founded Georgia, the last of the Thirteen Colonies, on a bluff overlooking the Savannah River about ten miles inland from the Atlantic Ocean. With Oglethorpe were more than one hundred colonists, including Georgia’s first craftsmen. It would be, as Oglethorpe observed in the promotional material for the colony, “a land of liberty and plenty.”1 Over the next century Georgia attracted a diverse mix of peoples. Many, like Oglethorpe’s first colonists, came from the British Isles seeking land and opportunity. Others, like the German Salzbergers, came to Georgia looking for freedom from religious persecution. Still others journeyed along the spine of the Appalachian Mountains, across the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia, to the Georgia Piedmont. Enslaved Africans and African Americans were brought to Georgia to power her emerging plantation economy. All the while Georgia’s Native American population was driven farther west. All of these peoples—European, American, African, and Native American—shaped the decorative arts of Georgia. Selections from the collection follow.

|

|

Paul Fourdrinier (d. 1758), A View of Savannah as It Stood the 29th of March 1734, London, 1734. Engraving, after a drawing by Noble Jones and George Jones (n.d.). 22 x 26½ inches. Gift of Frank L. Horton (5497). |

In November 1733 a draft of the town plan for Savannah, envisioned by James Edward Oglethorpe and drawn by Noble and George Jones, was sent to London to be engraved and included with the promotional material for the new colony. The ordered and egalitarian nature of the plan reflects Oglethorpe’s utopian vision for the colony as a place where downtrodden and oppressed Englishmen could make new lives. In depicting the highly regimented settlement against a background of dense wilderness, this print also suggests that the colonists, and their leaders, were adept at replacing the chaos of nature with European order.2

|  | |

| Left: Thomas Buford (ca. 1710–ca. 1774), James Edward Oglethorpe, London, ca. 1740. Mezzotint, 17¾ x 13½ inches. Gift of Frank L. Horton (2024.63). Right: John Faber the Younger (1684–1756), Tomochachi and Tooanahowl, London, ca. 1735. Engraving, after a painting by William Verelst (w. 1732– ca. 1756). Mezzotint, 17¾ x 8¾ inches. MESDA Purchase Fund (1142.2). | ||

Oglethrope and his colonists were not alone on the bluff they settled overlooking the Savannah River. Yamacraw, a Creek Indian village, was nearby. Its chief, Tomochachi (ca. 1644–1739) forged a close friendship with Oglethorpe. In 1735 the chief and his nephew Tooanahowi (ca. 1719–1743) accompanied Oglethorpe to London, where they had their portraits painted by William Verelst (w. 1732–ca. 1756). The portrait of the chief and his nephew was subsequently engraved. It is possible that at the same time Oglethorpe also had his portrait painted by Verelst, which later became the basis for his mezzotint portrait. It is tempting to see a symbolic relationship between Tomochaci’s deerskin and Oglethorpe’s ermine cape suggesting a dialogue between the peoples of the old and new worlds.3

|

Jar, attributed to Andrew Duché (1692–1762), Charleston, S.C., or Savannah, Ga., ca. 1735–1743 Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 131⁄16, W. 10½, D. 6 in. Gift of Frank L. Horton (3440) |

Though Georgia was founded for philanthropic reasons, its leaders also saw it as a money-making opportunity. In 1736 the colony encouraged Andrew Duché to establish a pottery in Savannah. Duché, the son of a Philadelphia potter of French Huguenot descent, made utilitarian earthenware like this pot, stamped with his initials. He also experimented with local kaolin clay deposits in an effort to make porcelain.4

|

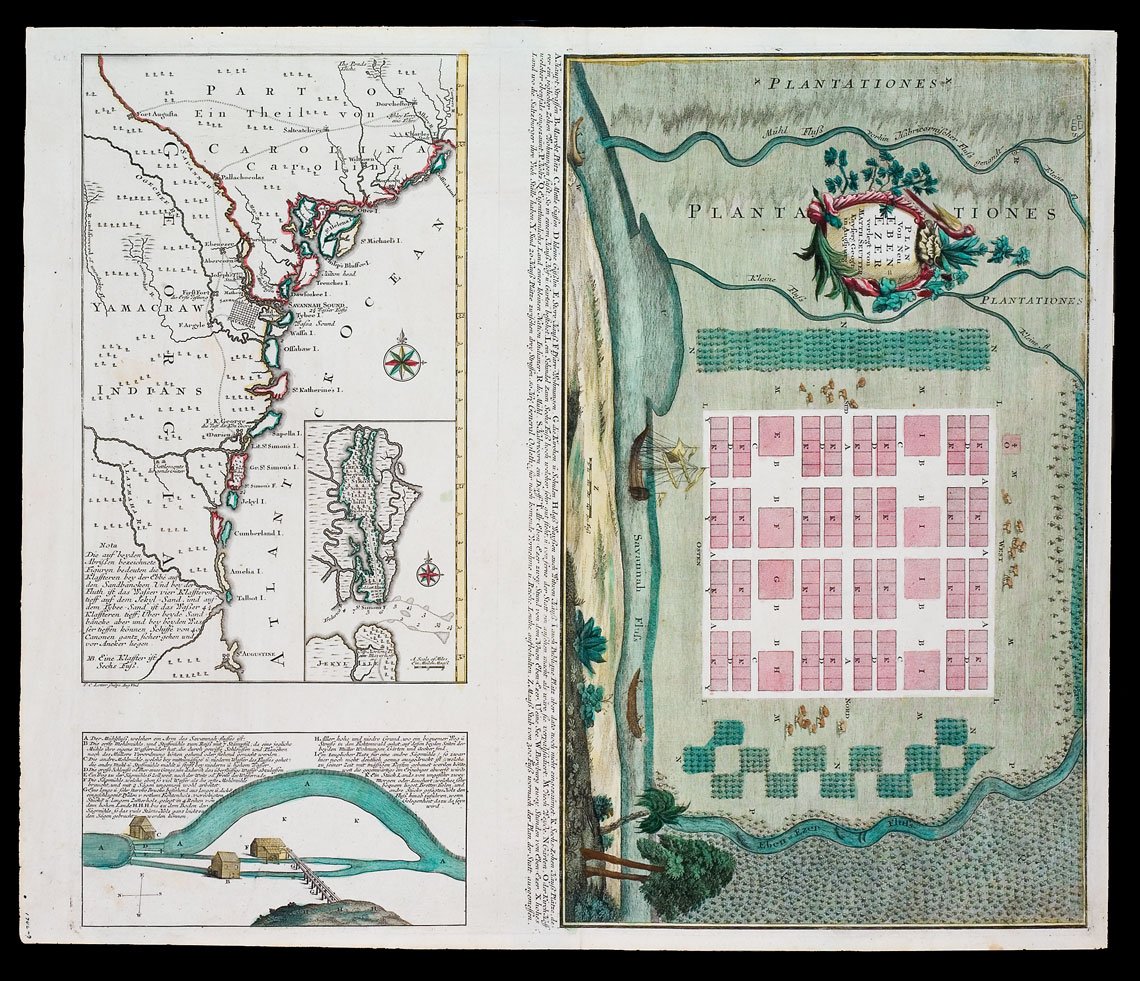

T. C. Lotter (1717–1777), Plan of Ebenezer, Augsburg, Germany, 1747. Engraving, after Matthew Seutter (1678–1757). 24 x 20¼ inches. Wm. B. Taliaferro Purchase Fund (2867). |

|

Stretcher table. Ebenezer, Ga., ca. 1735–1740. Sweetgum, yellow poplar, and yellow pine. H. 26, W. 32, D. 27½ in. MESDA Purchase Fund (2082). |

More than two centuries of religious conflict in Europe between Catholics and Protestants left thousands of people displaced from their homelands. Georgia’s trustees saw their colony as a refuge for displaced Protestants. In 1734 a group of German Salzburger refugees arrived in the colony and founded the city of Ebenezer upriver from Savannah.5 The plan of Ebenezer was closely modeled after Savannah with its orderly and egalitarian divisions of land. This map, published in Germany to entice further immigration, depicted the new settlement as a land of plenty, with orderly fields, river commerce moving along the town’s east side, and ample cattle grazing along the city’s north, south, and west boundaries.

Sulzberger craftsmen brought the Germanic traditions of their homeland with them to Georgia. This table (below), the earliest piece of Georgia furniture known, originated in the Sulzberger settlement and reflects the heritage and training of its maker in its baroque turnings and splay-legged form.

|

Sir George Houstoun, Artist unknown, Savannah, Ga., or London, England, 1775–1795. Watercolor on ivory portrait miniature (set in later gold mount). 1½ x 1¼ inches. Gift of Dr. Lucia Karnes and Jean R. Routh (3353.1). |

Sir George Houstoun (1744-1795) was born during Georgia’s final years of trusteeship under the Lord’s Proprietors and died a citizen of the United States. Like many Georgians, Houstoun prospered after the colony came under direct British rule in 1752 and limitations on the size of landholdings and the ownership of slaves were eliminated.

Houstoun had mixed feelings about the colony’s separation from Great Britain. In 1775 he joined the First Council of Safety to oversee the boycott of taxed British goods and was a member of Georgia’s first Secession Convention. Sometime around 1779 Houtoun switched allegiance, a change of heart for which he was heavily taxed following the Revolutionary War.

|

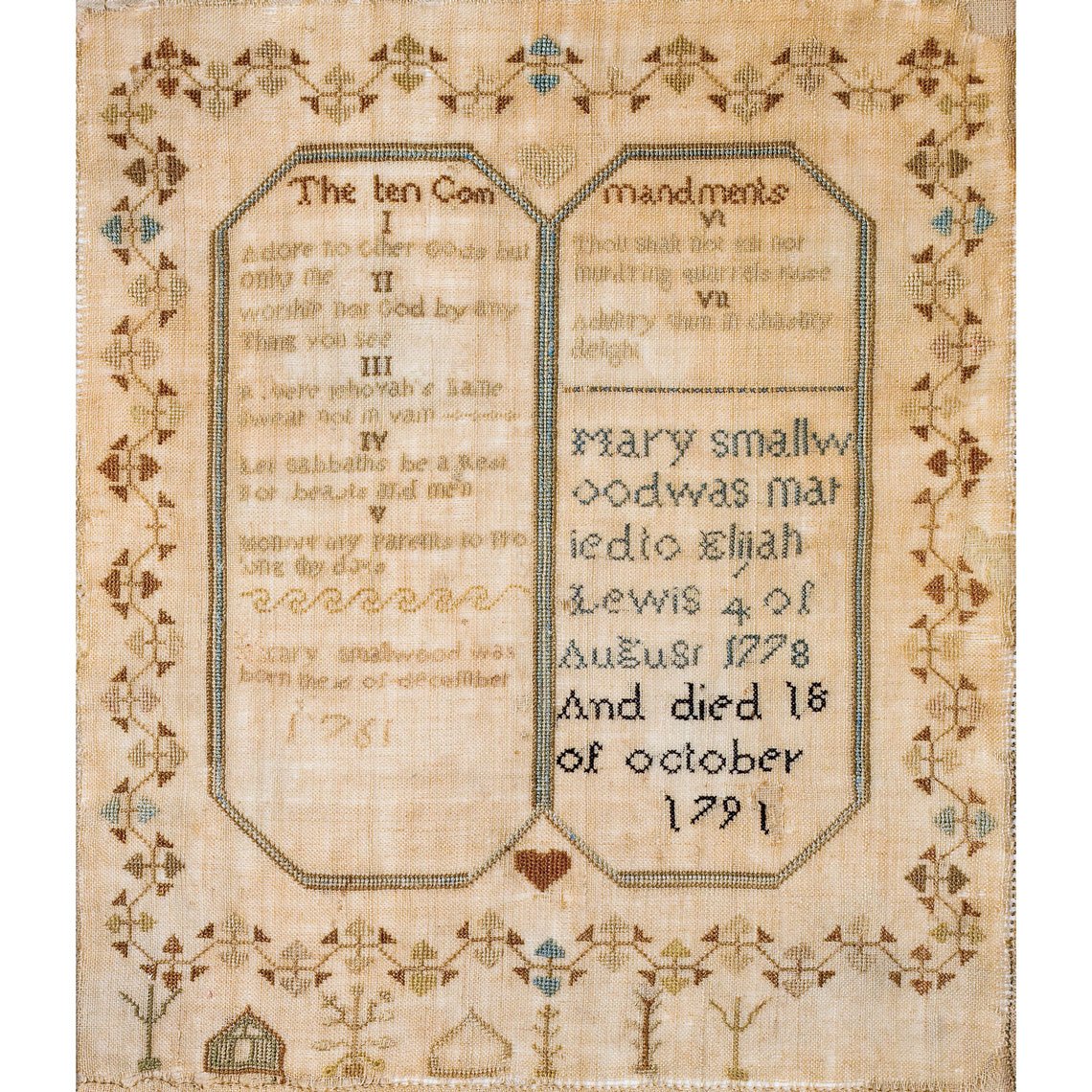

Sampler by Mary Smallwood (1761–1791), Liberty County, Ga., 1770–1778. Silk on linen. 15⅝ x W: 15½ inches. MESDA Purchase Fund (5504). |

Worked by Mary Smallwood of Liberty County, this is the earliest known Georgia sampler. Mary’s family was part of Liberty County’s sizeable Congregationalist community. Midway Congregational Church, where her family worshiped, was a hotbed of revolutionary fervor. The earliest independence gatherings in the state were held there, and two signers of the Declaration of Independence, Lyman Hall (1724–1790) and Button Gwinnett (1735–1777), worshipped there. Mary’s Ten Commandments sampler was left unfinished, presumably at the time of her 1778 marriage. When she died in 1791 an unknown hand recorded that fact in black thread at the bottom of the piece.

|

John Abbot (1751–ca. 1840). Painted Bunting (or Finch), Georgia, ca. 1792–1805. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 11 x 16½ inches. MESDA Purchase Fund (5503.4). |

John Abbot came to Georgia in 1776 and spent the following seven decades of his life recording the flora and fauna along the Savannah River. Several hundred of his watercolors were published in his The Natural History of the Rarer Lepidopterous Insects of Georgia (1797). Many thousands more became study objects in private collections of natural history. This watercolor of a painted bunting was purchased from Abbot for the collection of Chetham’s Library in Manchester, England. It was later sold by the library, became part of the Griffin collection, and was acquired by MESDA in May 2009.6

|

Sideboard, maker unknown, Augusta, Ga., 1800–1810. Birch, walnut, and yellow pine. H. 40½, W. 44⅞, D. 20⅝ in. MESDA Purchase Fund (2105). |

Augusta was the gateway to Georgia’s backcountry. Its location at the fall line of the Savannah River and the southern end of the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia made it attractive to Charleston and Savannah merchants and traders. Charleston fashions for display-oriented forms like this stage-top sideboard also spread inland to Augusta.7 Unlike its Charleston contemporaries, this sideboard features local walnut and birch instead of imported satinwood and mahogany.

|

Corner cupboard, maker unknown, Oglethorpe County, Ga., 1845–1855. Yellow pine with paint. H. 86¾, W. 44, D. 24 in. MESDA Purchase Fund (5422). |

Born in Columbia County, Georgia, Augustus Dozier (1807–1902) settled in nearby Oglethorpe County following his marriage. Primarily a farmer, Dozier also worked as a land surveyor. On the eve of the Civil War he owned 750 acres of land and eighteen slaves, placing him well within Georgia’s upper middle class.8 Around 1840 Dozier built a house for his family that would become known as White Oak plantation. This corner cupboard was part of its original furnishings.9 Entirely of yellow pine, and grain painted to resemble mahogany, it was part of an elaborate scheme of faux finishes at the plantation. Research by independent scholar Linda Crowe Chestnut and preservation consultant Maryellen Higgenbotham of MESDA has revealed evidence of grain painting on the house’s doors, mantles, and wainscoting

|  | |

| Left: Charles Bird King (1785–1862), Mistipee, Yoholo-Micco’s Son, Washington, D.C., 1825. Oil on canvas, 17½ x 14¼ inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James W. Douglas (3542). Right: Henry Inman (1801–1846), Mistippee, Yoholo-Micco’s Son. After paintings by Charles Bird King, Philadelphia, Pa., 1837–1844. Lithograph, 1913⁄16 x 1313⁄16 inches. MESDA Purchase Fund (5507.1-2). | ||

During the early nineteenth century, waves of settlers sweeping into Georgia’s backcountry pushed the Cherokee and Creek Nations farther west. By the 1820s both nations were regularly sending delegations to Washington to protest illegal encroachment on their tribal lands. Thomas Lorraine McKenney (1785–1859), the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, was sympathetic to their claims but found that he could do little to stop settlement. Desperate to document a vanishing way of life, McKenney commissioned the artist Charles Bird King to paint portraits of the visiting dignitaries.

In 1830 McKenney was fired by President Andrew Jackson. Following his dismissal, McKenney had the portraits secretly copied by the artist Henry Inman and taken to Philadelphia where they were published as a three-volume History of the Indian Tribes of North America. Most of Bird’s original paintings burned in a fire in 1865.10 MESDA is fortunate to own one of the few surviving Native American portraits by Bird.

|

The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts will host its biennial MESDA Conference on American Material Culture, October 28–30, 2010, at the Madison-Morgan Cultural Center in Madison, Georgia. The only major scholarly forum for American material culture and decorative arts, the conference will feature a keynote lecture by Dr. Bernard L. Herman, the George B. Tindall Professor of American Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, followed by a full day of scholarship moderated by Dr. Herman, Dr. Maurie D. McInnis, associate professor of Art History at the University of Virginia, and Dale L. Couch, adjunct curator of decorative arts at the Georgia Museum of Art. The final day will explore the Georgia Piedmont, with field trips to museum and private collections. The conference will coincide with a special exhibit at the Madison-Morgan cultural center curated by Mr. Coach that explores the ethnic and cultural evolution of an important and unique group of middle Georgia chairs. For more information call 336.721.7360 or visit www.MESDA.org/conference.

1. James Edward Oglethorpe, A New and Accurate Account of the Provinces of South-Carolina and Georgia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2004). See http://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/oglethorpe/oglethorpe.html.

2. Margaret Beck Pritchard. “Useful Devices: The Prints and Maps at MESDA,” The Magazine Antiques (January 2007): 208.

3. Ibid.

4. See Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter ‘a Little Too Much Addicted to Politicks,’” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 1, (May 1991).

5. For more on the settlement at Ebenezer see George Fenwick Jones, The Georgia Dutch: From the Rhine and Danube to the Savannah, 1733–1783 (Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press, 1992).

6. Vivian Rogers-Price, John Abbot’s Birds of Georgia: Selected Drawings from The Houghton Library Harvard University (Savannah, GA: Beehive Press, 1997), vii–xxiii.

7. For examples of this fashion in Charleston see Bradford L. Rauschenberg and John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Charleston 1680–1820, vol. II, (Winston-Salem, NC: The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 2003), 645–655.

8. Ibid, 60-61.

9. Ibid, 62.

10. See Herman J. Viola, The Indian Legacy of Charles Bird King (Washington. DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1976).

Daniel Kurt Ackermann is associate curator of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem Museum & Gardens, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|