Last November, Andy Warhol's 1962 painting "Men in Her Life" sold for over $60 million at Phillips de Pury & Co. It went for well over its high estimate, and became the second most expensive Warhol painting ever to sell at public auction. Because both the buyer and the under bidder were on the phone, the scenario was ripe for speculation. Some market observers and journalists wondered if there had been foul play, and talk arose, as it does from time to time, that the fast-paced, loosey-goosey art market was in need of regulation.

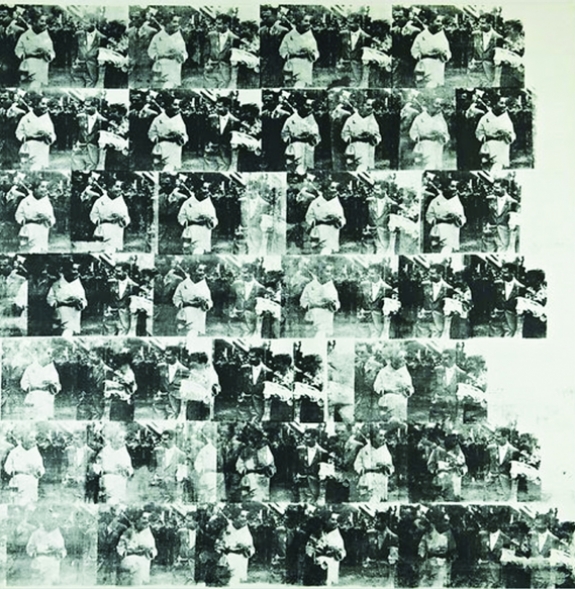

With the major biannual contemporary art sales at Christie's, Sotheby's and Phillips once again upon us, it's worth remembering the fuss over Warhol's 82-inch painting which, through a single, repeated photographic image, tells the story of a famous love triangle. Liz Taylor is at a racetrack squeezed between her movie producer husband Mike Todd and his best friend, crooner Eddie Fisher, who was then married to starlet Debbie Reynolds. Todd's marriage to the beautiful Taylor, then a dewy 24, was his third; when he died in a plane crash in 1958 it would take less than a year for Fisher to dump his own spouse, hook up with his dead friend's young widow and marry her in 1959. As it turned out, this spelled doom for Fisher, because his clean-cut showbiz persona was, in part, dependent on a storybook-perfect marriage to the wholesome Reynolds. It wasn't long before the unfavorable publicity surrounding his affair and divorce prompted cancellation of his television series with NBC and his recording contract with RCA. By 1964, his marriage to Taylor had also ended. Warhol's painting captures the beginning of what would be a series of disasters for both men.

The same week that Philips sold "Men in Her Life," Sothebys's sold a large 1962 Warhol painting, "Coca-Cola [4] Large Coca-Cola," for $35 million. They are both from the artist's early, and most valuable, period, but for me the similarity between them ends there: the Coca Cola bottle is merely a great hand-painted early pop image, whereas the newspaper-appropriated image of Liz's love triangle is representative of Warhol's most important contribution to art history, and well worth double what the other painting sold for.

All it takes is two bidders to chase a painting well past its presale estimate, and nowhere in any catalog does it say, "Please don't overpay." Do we really need a regulation setting these prices in their appropriate ratios to insure that clients don't overpay? Auctions today are about theater. Face it: it's pretty amazing to see such large quantities of money lavished on works of art whose value is strictly subjective. No matter how great they are, they aren't gold mines or oil wells.

As much as I love Warhol, the blockbuster prices at the high end feel like they're topping out. This season yet another large Warhol "Fright Wig" self-portrait comes up at auction, and once again it has been dubbed "the last in private hands." This blazing red one from collectors Norah and Norman Stone of San Francisco carries a $40 million price (a purple one made $32.5 million last year). Also on offer is a blue Liz, estimated at over $20 million, and an assemblage of "16 Jackies" priced at $25 million. There is little oxygen in the upper reaches of this market, but eventually a picture will crash and the cycle will turn or slow down. Until that happens, the auction experts will continue to source the material and find the clients, season after season. But then again, maybe it won't happen. Maybe, like Columbus, we'll find that the world of demand for Warhol is bigger than we thought it was. Meanwhile, the sums traded for these top lots are staggering, and the brouhaha surrounding them adds to the conviction of some that regulation lurks just around the corner.

The last time the government interfered in the art market was after the scandal over the price-fixing arrangement between Sotheby's and Christie's. It's been over 10 years since this debacle, and still the pain is fresh. Remember when Christopher Davidge, then CEO of Christie's, ratted out his competitor, Sotheby's, took $7 million in severance and jetted off with the young, attractive Asian art specialist Amrhita Jhaveri? Both Christie's chairman Sir Anthony Tennant and Sotheby's chairman Alfred Taubman were found guilty of price fixing under U.S. antitrust laws, but only Mr. Taubman was incarcerated — he spent 10 months in prison — because there is no applicable criminal law in the U.K.