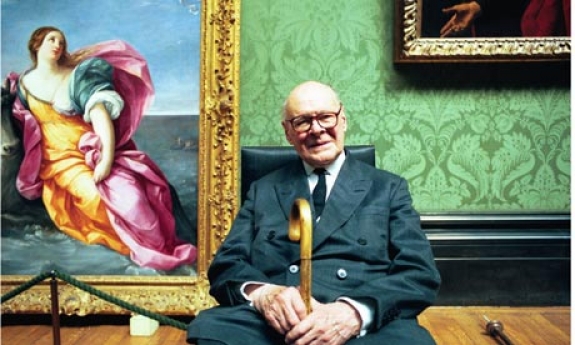

Sir Denis Mahon, who has died aged 100, was one of the most distinguished art historians and collectors of the 20th century, and a determined campaigner on behalf of museums into his 90s. His collection of Italian baroque paintings, including masterpieces by Guercino, Guido Reni and Luca Giordano, has been deposited in British institutions, including the National Gallery in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh.

Twice a trustee of the National Gallery (1957-64, 1966-73), he was instrumental in pushing through several important acquisitions, including Reni's Adoration of the Shepherds, still the largest painting in the gallery, and, in 1970 (with the much-appreciated support of the sculptor Henry Moore, a fellow trustee), Caravaggio's Salome Receives the Head of St John the Baptist, a very moving late work by the artist. He was a zealous guardian of the public interest, actively opposing the imposition of charges for visitors to museums and lobbying for legislation to prevent the National Gallery from selling any of its pictures.

Together with the National Art Collections Fund (now the Art Fund) and others, he pressed for the conversion of the Land Fund – set up in 1946 as a memorial to those who had given their lives for their country and which had then been conveniently forgotten, as he put it, by the Treasury – into the National Heritage Memorial Fund, with independent trustees. His collection was always a very effective weapon in these campaigns, and he several times threatened to dispose of it abroad if the government of the day, Labour or Conservative, failed to live up to its responsiblities in defence of museums and heritage.

His natural attitude towards ministers and bureaucrats was one of suspicion, and theirs towards him was one of respectful fear combined with intense exasperation. He did, however, have a good working relationship with several arts ministers, including the Conservative Grey Gowrie (1983-85) and the Labour culture secretary Chris Smith (1997-2001).

Even after making public the details of his decision in 1999 to bequeath his pictures to the national collections fund, with the instruction that they be deposited in various British galleries and museums, he still threatened to change his arrangements if the government refused to change the rule whereby the non-charging national museums – including the British Museum, National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery – could not reclaim VAT, whereas the charging museums – the Victoria and Albert, Natural History and Science Museums – could. In 2001 the government agreed to remove the anomaly, a gesture that gave Mahon real pleasure.

Born in London, he was the the son of John FitzGerald Mahon, a member of the family that had prospered from the Guinness Mahon merchant bank, and the grandson, through his mother, Lady Alice Evelyn Browne, of the fifth Marquess of Sligo. On visits with me to Kenwood House, on Hampstead Heath, north London, he would point out with evident satisfaction that the Portrait of Countess Howe, one of Thomas Gainsborough's finest paintings, showed his great-great-great-grandmother.

Educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford, where he read history, Mahon developed a great enthusiasm for opera. A career in the family business held little attraction for him, and he soon decided to devote himself wholly, and to the exclusion of the pleasures of opera, to studying the history of art. Kenneth Clark, then at the Ashmolean, was an influential figure in his formative years and recommended him to Nikolaus Pevsner, the German émigré art historian, who was then teaching at the fledgling Courtauld Institute of Art in London.

Best known today for his writings on the architectural history of Britain, Pevsner had early been interested in Italian baroque art, and suggested to Mahon that he study the work of Guercino – the little squinter – the nickname of Giovanni Francesco Barbieri, a neglected Bolognese painter of the 17th century. Guercino was an ideal subject because his life is well documented, and he was remarkably well represented in British collections. The largest group of drawings by him is at Windsor Castle, in the Royal Collection, which Mahon was to catalogue, together with Nicholas Turner, in 1989.

In his 20s, Mahon travelled extensively to study the works in museums and private collections of the Bolognese painters: the Carraccis – the brothers Annibale and Agostino, and their cousin Ludovico, who were jointly responsible for a revival of Italian painting at the end of the 16th century – Reni and, of course, Guercino, who remained his principal interest throughout his life.

Together with the Viennese expert Otto Kurz, another member of the diaspora of Jewish art historians who had left Germany and Austria in the 1930s, he visited Stalinist Russia, with a trunk of full of antiquarian books, including the biographies of artists written in the 17th century by Gian Pietro Bellori and Carlo Cesare Malvasia. The customs officials demanded that the English newsprint that had been used to wrap up the books be removed and handed in to the authorities, and informed them that they could claim it back when they left.