Schoolgirl Art from the Misses Martin’s School for Young Ladies in Portland, Maine

|

| Fig. 1: Attributed to Anna M. Bucknam, Congress Street, Portland in 1824, Portland, Me., 1832 watermark. Watercolor on paper, 14-3/4 x 19-1/2 inches. Courtesy, Maine Historical Society and Maine State Museum (1998.30.1). The city served as the state capital after Maine separated from Massachusetts in 1820 until 1832. The new state house, the white classical building on the right, sits next to the Cumberland County Court House. The Portland Academy, another of the city’s notable private schools, is the three-story brick building at left. |

The Misses Martin’s School for Young Ladies in Portland, Maine, was an important source for some of Federal America’s finest schoolgirl art. A distinctive group of objects, including embroidered silk pictures and paint-decorated tables, can be documented to some students, and attributed to others, attending what was one of New England’s foremost academies.

William Martin (1733–1814), a member of an aristocratic British family, founded the school in 1803. Earlier in life when his father died young, Martin was left “very ill provided for.” Instead of following his father’s footsteps at Cambridge University, he became a London merchant. Though initially finding prosperity, Martin met financial misfortune and, like many of his countrymen adversely affected by shortages and poor economic conditions resulting from the Revolutionary War, he decided to relocate to America.1 In 1783, Martin, his wife, Elizabeth Galpine (1739–1829), and six children settled in Boston, Massachusetts, where Martin imported and sold “a choice parcel of Books, and late Magazines and Reviews,” along with an extensive assortment of textiles, filling pent-up demand for British goods.2

|

| Fig. 2: Photograph of the Storer-Mussey house, Portland, Me., late nineteenth century. Demolished 1962. Courtesy, Maine Historic Preservation Commission. Designed by the Portland architect Alexander Parris (1780–1852) in 1801, Storer’s spacious residence was one of the town’s finest homes. After Storer lost it following the 1807 embargo, the Martins rented it from the Portland Bank, occupying it for almost ten years until August 1817 when merchant John Mussey bought it. Rachel Lambard painted her table while boarding in this elegant Federal residence. |

Naturalized in 1787, William Martin moved with his family to Maine, a district of Massachusetts until statehood was achieved in 1820. In 1787, he purchased the estate of Jeremiah Powell, comprising more than three hundred acres and a shipyard on Broad Cove in North Yarmouth, Maine. Martin set up in trade and quickly gained regard in his community. While representing North Yarmouth in the General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts between 1792 and 1797, Martin’s many committee activities included legislation to establish Bowdoin College in 1794; he served as a charter trustee. Financial troubles continued to plague him, however, and another source of income was required to sustain the family. Late in 1803 the Martins opened their school in North Yarmouth, with their “genteel house,” several outbuildings, a large garden, and orchards with European fruit trees, but with the intention, according to Penelope Martin, of moving into Portland, ten miles south, the following spring.3

| |

| Fig. 3: In the style of George Engleheart, Penelope Martin, daughter of Mrs. William Martin, London, England, circa 1787. Watercolor on ivory in gold mount, 1-13/16 x 1-7/16 inches. Courtesy, Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Bequest of William Martin Payson in memory of the Martin family (1921.19.2). |

Portland was steadily recovering from its Revolutionary War naval bombardment and growing into a commercial and cultural center (Fig. 1). The family rented properties in the then-fashionable High Street neighborhood and their school was always located in their home. In 1805, they leased the Ann Street residence on the Fore River that recently had been vacated by the enterprising but now bankrupt Thomas Robison, the patron of cabinetmaker, John Seymour.4 Penelope Martin recalled Robison’s property as “very large, convenient, pleasant, retired, and possessed a delightful garden, which proved salutary and agreeable to our Scholars.” The school increased rapidly and here they accommodated thirty-three boarding students.5

In 1808 the Martins moved up the hill one block to rent the Ebenezer Storer house (Fig. 2). Parents were charged forty dollars per quarter for board and tuition, with extra fees for supplies and a “seat in the meeting house.”6 At the Storer house, they began to admit day scholars in 1812. Finally, in 1817 they purchased a Portland home of their own on India Street; it, too, had a “pleasant garden in the rear.” Business began to diminish by 1821, but the school continued until shortly after family members received a generous legacy from British relatives in 1832; it had been in operation for thirty years.7

At least four of Martin’s children were involved with the school. The eldest, Catherine (1765–1860) and brother, William Clarke (1769–1849), managed daily operations. Penelope (1773–1859) and Elizabeth (1778–1844) taught, with Penelope (Fig. 3) recognized as preceptress, the school’s central figure. When her family emigrated, Penelope had stayed behind in London to complete her education, attending her aunt’s boarding school where she helped younger students with their lessons; she joined her family in Maine in 1790.8 Edward Elwell, Portland’s nineteenth-century historian who knew the Martins, observed that the Misses Martin were “cultivated English ladies and brought with them the customs and traditions of their own teaching at home. English branches were taught, a little French, music, painting and many kinds of fancywork, lace making and filigree, also geography with the use of globes. They were very successful and theirs was the fashionable school of the day.”9

|

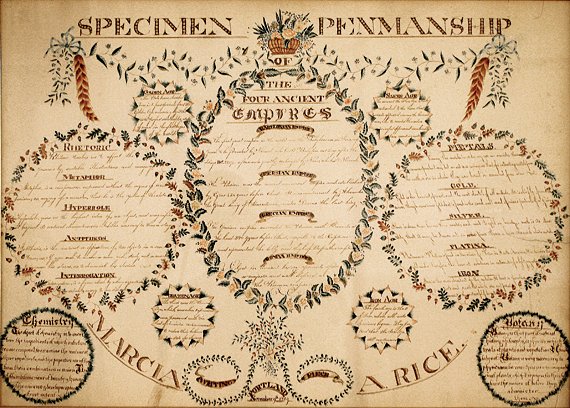

| Fig 4: Marcia Adeline Rice (1803–1832), Specimen of Penmanship, Portland, Me., dated November 9, 1819. Pen and ink and watercolor on paper, 23 x 31-1/4 inches. Courtesy, Maine Historical Society (1990.122). |

The school’s students and operations can be documented in two invaluable primary sources. Fulfilling a request from many of their patrons, the Martins published a List of Young Ladies Who Attended the Misses Martin’s School, from 1804 to 1829, recording the names of over five hundred boarding and day students from Maine, New Hampshire, and New Brunswick, as well as Boston and as far south as Honduras.10 Although the Martins sometimes omitted the given names or hometowns of some students and misspelled others, the List is a remarkable document that, with continued research, would help link artwork with students attending the school, not unlike Jane Nylander’s database for Mrs. Rowson’s Academy in Boston.11

The second documentary source is Penelope Martin’s memoir, written between 1821 and 1824, when she was “incited to preserve some memorial of this truly interesting period...lest...[it] should be consigned to oblivion.” She focused on the rigors of teaching and her duty to her family’s success rather than recounting daily life at the school. The workload of her young charges sometimes drew complaints from them or criticism from their protective parents. Notably, she encouraged the more talented students to “carry home several specimens of improvement.”12 Of the innumerable drawings, embroideries, and other works that must have been completed, schoolgirl art attributed to thirteen Martin students has been identified to date. They include eight silk embroidered pictures, two watercolor drawings, and four examples of decorative painting on wood.13 Nine were made by girls whose names and hometowns are itemized in the Martins’ List.The others are attributed to the Martin school based on family associations, their closely related designs and style of execution, and other sources.

|

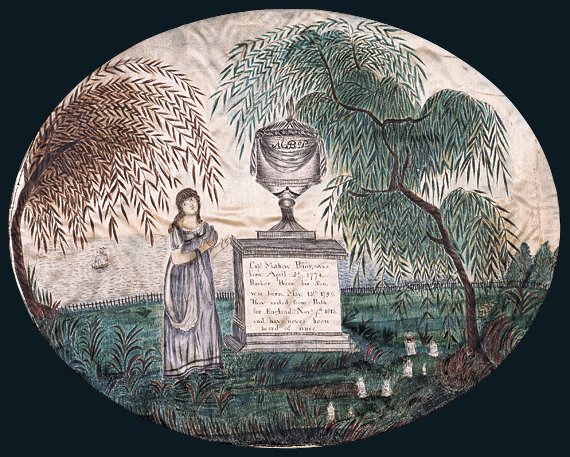

| Fig. 5: Attributed to Jane Otis Prior (1803–after May 31, 1880), Mourning Piece for Captain Mathew Prior and His Son Barker,Portland, Me., ca. 1819–1822. Watercolor, pencil and ink on silk, 13-5/8 x 17-7/8 inches. Courtesy, American Folk Art Museum (1992.25.1). Jane’s exceptional memorial is dedicated to her father and brother who sailed from Bath, Maine, to England in 1815 and were lost at sea. It probably dates within the final years of her Martin school education. |

In addition to their general studies in reading and geography, students practiced penmanship because any inked design required facility with a pen. “If you would win a Pen of Gold, Learn First of all your Pen to Hold,” exhorted John Jenkins in his 1813 edition of The Art of Writing, where he explained the requirements for fine penmanship and illustrated different types of lettering and their specific uses.14 Miss Martin recollected in her memoir that during their public exhibitions, “we had the approbation of Gentlemen of the greatest respectability and learning.” Surely they would have admired Marcia Rice’s large Specimen of Penmanship, displaying various styles of lettering, including plain block letters and elegant “German text,” prized for its ornamental qualities (Fig. 4).15

A beautiful memorial picture, drawn and painted on silk and attributed to Jane Otis Prior, was among the first objects to be identified with the Martin school (Fig. 5). The older sister of artist William Matthew Prior (1806–1873), Prior’s name appeared in Martin’s List.16 It is unusual in that its painted scene is in the style of silk embroidery. Its finely drawn elements relate to those found in Sarah Hart’s 1817 picture that combines embroidered trees and costumes in a landscape painted on silk with penwork details. More fully embroidered silk pictures by Harriet Cutter entitled Lily and Rose (Fig. 6), Mary Ingraham’s Holy Family, and Nancy Myrick’s La Chatte Merveilleuse, featuring figures in naturalistic scenes with trees and flowers, reveal the high quality produced at the Martin school. Harriet Cutter’s pattern, Lily and Rose, is identified by block letters printed on the silk under the frame’s rabbet. This same scene, with slight differences, was worked by three other girls, two of whom may be identifiable by the initials they included on the pages of an open book in their scene.17

|

| Fig. 6: Attributed to Harriet Cutter (1800–1863), Lily and Rose, Portland, Me., ca. 1817. Silk and watercolor, 19 x 21-1/2 inches (with frame). Courtesy, Maine Historical Society (2009.205). |

|

| Fig. 7: Box, decorated by Jane Otis Prior (1803–after May 31, 1880), Portland, Me., dated 1822. Birch, H. 4-3/8, W. 12, D. 7-3/4 in. Courtesy, Maine State Museum, gift of Elizabeth Noyce (1994.119.1). On the front between musical trophies, Prior inscribed the name of her friend and Martin schoolmate, “Sarah McCobb.” The box is further painted with four landscapes, three of which were based on published prints. |

The Martins also taught the art of painting on wood, as the decoration was then known. Figured maple or birch, in imitation of Asian satinwood often used for fine painted English furniture, acted as a canvas for what appears to be water-based paints. Jane Prior’s covered box was the key to establishing the Martin school as a source for this charming type of furniture (Fig. 7). Similarly decorated tables and boxes are documented to other New England female academies, including Mrs. Rowson’s in Boston. Rowson, like the Martins, emigrated to the United States from London following the Revolutionary War, and operated one of the early Republic’s finest schools.18 The Martin objects, however, comprise an unusually large body of painted schoolgirl furniture associated with a single New England academy.

| |

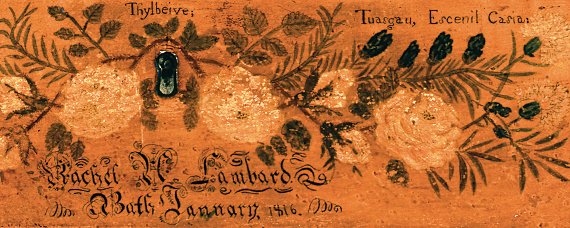

| Fig. 8: Chamber table, decorated by Rachel A. Lambard (m. 1818), Portland, Me., dated January, 1816. Maple, birch, pine, H. 33, W. 32-1/8, D. 16-3/4 in. Courtesy, Winterthur Museum and Library (57.985). Rachel Lambard was one of two daughters of Luke Lambard of Bath, Maine, who are believed to have attended the Martin school. Her penmanship, copied prints, and freehand painting exhibit the exuberant range of decoration found on this group of furniture attributed to the Martin school. |

Three chamber tables, all signed and dated 1815 and 1816, are attributed to the Martin school based on documentary evidence and the connoisseurship of the objects.19 One of the tables was painted by Rachel A. Lambard (Fig. 8); another by her sister, Elizabeth Paine Lambard, now in the Shelburne Museum; and the third by Wealthy Bradford Jones, also at the Winterthur Museum. Like Prior’s box, their decoration ranges from carefully penned inscriptions and poems to painted landscape scenes and delicate flowers, birds, and seashells. Their designs follow the same format: a central scene on the top is framed by smaller decorative elements, small landscapes appear on the sides, and India ink inscriptions decorate the fronts. Leaves entwine the tables’ legs. The students used simply penned letters for inscriptions, anagrams, poems, and the outlines and frames within their drawings. “Square hands,” a popular lettering style so-called because it was easily shaped with a wide metal nib, appears in many inscriptions as does elegant “German Text.” The bold verticals of these ornamental capital letters required a wide nib; their flourishes were added with a fine copperplate pen (Fig. 9).

The principal design elements are the naturalistic images and landscapes, most often copied from English and American prints. The countless drawings of romantic landscapes or ruins, signed by schoolgirls throughout the Eastern Seaboard, testify to the popularity of copying prints from books and periodicals. The Boston State House appears on the cover of Prior’s box (Fig. 10); the Village of Egington in Bedfordshire and Hendon Park, Northumberland, decorate two sides. Limerick Castle in Ireland fills Rachel Lambard’s table top (see Fig. 8) and she included views of The Rotunda in the Gardens of Stourhead in Wiltshire and A Part of Netley Abbey in Hampshire on the side skirts. All were based on published images.20 Jane Prior is noteworthy because she also incorporated a unique original composition inscribed “Sketch of Thomaston, Maine, Front Street” on the back of her box (Fig. 11).

|

| Fig. 9: Detail showing Lambard’s inscription on the drawer front of chamber table seen in figure 8. |

Rachel Lambard decorated every inch of her table with three poems, three landscapes, four inscriptions, nine anagrams, many phrases and poetry extracts, twelve songbirds, and a bounty of flowers. She was determined to show her parents everything she had learned. The lines “Wishing of all employments is the worst. Learn! Know Thyself! All wisdom centers here,” are from Night Thoughts, the popular poem by Edward Young (1681–1765). Penelope Martin recalled that her father “took great pleasure in teaching [the scholars] to read, and recite with propriety, the best of poets, especially [John] Milton and Young.”21

During the time that Rachel Lambard and Jane Prior were at school, published manuals aiding students in the art of drawing were becoming widespread. Henry Williams, an itinerant artist who had visited Portland, published Elements of Drawing in 1814. Widely circulated until 1830, it is not surprising to find it advertised for sale in Portland newspapers along with brushes, paints, and paint boxes.22 François Louis Thomas Francia and John Hill’s A Series of Progressive Lessons, Intended to Elucidate the Art of Flower Painting in Water Colours, published in four editions between 1815 and 1835, gave more specific instruction on the execution and coloring of leaves and blossoms, a variety of which appear on the tables.23

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 10: Detail showing Prior’s drawing of the Boston State House on the box seen in figure 7. Right: Fig. 11: Detail of box seen in figure 7. Prior created a unique composition of Thomaston, a shipbuilding town east of Bath, Maine, where she and her classmates had family and friends. Around the top’s edge, Prior depicted a row of shells, each set against seaweed or red coral. The helmets, whelks, moon shells, and tritons, native to the Eastern seaboard and Caribbean, might have been copies from books, such as Burrow’s Elements of Conchology of 1815, advertised for sale in Massachusetts. However, original specimens would have been available locally, collected by Portlanders who made voyages carrying lumber to any number of southern ports. | ||

Given the popularity of the manuals, the designs of the Martin painted tables, and William Martin’s interest in books, the Martin students may have had access to volumes such as these, but the gardens at the Martin school themselves were a source of inspiration.

With continued research, new works may be ascribed to this remarkable school. Research would also advance our understanding of the school’s influence in early nineteenth-century New England so, like those better-known Massachusetts schools of Mrs. Rowson and Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach in Dorchester, the Martin school will attain its rightful place in the study of American decorative arts.

1. Edward Payson Payson, “William Martin, Esq.,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register 54 (1900): 30–31.

2. American Herald (Boston, Mass.), May 2, 1785.

3. Payson, “William Martin,” 30–31; Cumberland County Registry of Deeds, Portland, Me., vol. 15: 309–310. Columbian Centinel (Boston, Mass.), March 1, 1800. Penelope Martin, Memoir, 1821–1824, Maine Women Writers’ Collection, University of New England.

4. See Laura F. Sprague, “John Seymour and Family in Portland, Maine,” in Robert D. Mussey, Jr., The Furniture Masterworks of John and Thomas Seymour (Salem, Mass., Peabody Essex Museum, 2003), 17–18.

5. Martin, Memoir.

6. Invoice, Penelope Martin and sisters to Malatiah Jordan, [November] 1814, Peters Family Collection, Maine Historical Society.

7. Martin, Memoir. Edward Elwell, The Schools of Portland (Portland, Me.: Wm. M. Marks, 1888), 33.

8. Bennett-Martin monument, Evergreen Cemetery, Portland, Maine. Elizabeth Sweetser Baxter, comp., Penelope Martin: An Ornament of Grace (Cumberland, Me.: Cumberland Historical Society, 1990). William Willis, ed., Journals of the Rev. Thomas Smith, and the Rev. Samuel Dean, Pastors of the First Parish Church, Portland (Portland, Me.: Joseph S. Bailey, 1849), 405. Martin, Memoir.

9. Elwell, Schools of Portland, 33.

10. List of Young Ladies Who Attended the Misses Martin’s School ([Portland, Me.], n.d.), Maine Historical Society.

11. Jane C. Nylander, “Useful and Ornamental Education for Young Ladies: Mrs. Rowson’s Academy, Boston, 1797–1822,” New England Ancestors 7, no. 1 (2006): 19–26, 51, and its companion database at New England Historic Genealogical Society (www.americanancestors.org).

12. Martin, Memoir. Her descriptions of the school’s philosophy and operations are similar to those found at the Rowson school; see Nylander, “Mrs. Rowson’s Academy,” 20–22, 24.

13. Betty Ring identified four silk pictures in Girlhood Embroidery, American Samplers and Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850, 2 vols. (New York, N.Y.: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), 1:250–253. Jane Nylander kindly brought the 1817 needlework picture by Sarah Hart at Historic New England to my attention (2004.26.493). The eighth, attributed to an unidentified student, appeared in Jackie Radwin’s shop inventory, San Antonio, Tx., see http://www.antiquesandfineart.com/dealers/item.cfm?id=103&pid=9172&pg=1. The location of Eliza Smith’s A New Map of the Terrestrial Globe is presently unknown.

14. John Jenks, The Art of Writing Reduced to the Plain and Easy System (Cambridge, Mass.: Printed for the Author, 1813).

15. Ambrose Serle, The Art of Writing (London: Printed for George Keith, 1782), 16. Portland Room, Portland Public Library.

16. List of Young Ladies. Sheila Rideout of Wiscasset, Me., owned Prior’s mourning picture in 1986 and identified her as a Martin student. Stacy Hollander and Brooke Davis Anderson, American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (New York, N. Y.: Abrams, 2001), 309.

17. Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 1: 251–253. Myrick’s picture is illustrated in Beatrix T. Rumford, general ed., American Folk Paintings: Paintings and Drawings other than Portraits from the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Center (Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown, & Co., 1988), 378.

18. Jane C. Giffen, “Susanna Rowson and Her Academy,” The Magazine Antiques 98, no. 3 (September 1970), 440. Nina Fletcher Little, Country Arts in Early American Homes (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1975), 86, 88.

19. Charles F. Montgomery, American Furniture: The Federal Period in the Winterthur Museum(New York: Viking Press, 1966), 462–463. Alfred T. Holt, M.D., comp., “Bath Families in the 19th century” (Bath, Me., Patten Library manuscript, 1984–2001). Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts, 1790–1840 (Milwaukee, Wisc.: Chipstone Foundation, 2004), 28–29; Nina Fletcher Little, Neat and Tidy: Boxes and Their Contents Used in Early American Households (New York: E. P. Dutton Books, 1980), 136.

20. Prior’s Boston State House may be based on Abiel Bowen’s 1817 print. For Netley Abbey, see John Britton and Edward Wedlake Brayley, The Beauty of England and Wales, or Delineations, Topographical, Historical, and Descriptive, of Each County: Embellished with Engravings, 18 vols. (London: Printed by Thomas Maiden, 1801-1815), 6: plate opposite p. 151.

21. Priddy, American Fancy, 28–29; Martin, Memoir.

22. Eastern Argus (Portland, Me.), December 9, 1803; Teaching America to Draw: Instructional Manuals and Ephemera, 1794–1925 (University Park, Pa,: Pennsylvania State University Libraries, 2006), 4. Henry Williams, Elements of Drawing (Boston, Mass.: R. P. & Co. Williams, 1818), 9. Eastern Argus (Portland, Me.), June 12, 1821.

23. François Louis Thomas Francia and John Hill, A Series of Progressive Lessons, Intended to Elucidate the Art of Flower Painting in Water Colours (Philadelphia, Penn.: Desilver, Thomas & Co., 1835), plates 1–2, American Antiquarian Society.

Laura Fecych Sprague, an independent curator, serves as consulting curator of decorative arts at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Me. The author gratefully acknowledges the Winterthur Museum and Library for the 2007 fellowship that supported this research.

This article was originally published in the Summer/Autumn 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|