|

|||

|

by Charles Brock and Nancy Anderson, with Harry Cooper

|

|||

| The early American modernists may be usefully understood as the generation of artists born primarily between 1875 and 1890 who promulgated the new languages of modern art—fauvism, cubism, futurism, orphism, synchromism, expressionism, Dada—both in the United States and abroad. This remarkably small group constituted a true avant-garde; over the course of the twentieth century legions of artists would follow in their wake. Yet as the century unfolded, the contribution of these painters and sculptors to the history of modernism was at times illuminated and at other times obscured. A point of near total eclipse was reached after World War II, with the promotion of abstract expressionism as the ultimate “triumph” of American painting. During the last quarter of the twentieth century, a clearer vision emerged of the early American modernists’ crucial role in the development of a modernist culture both in America and Europe. The Shein Collection, consisting of twenty representative works by nineteen of the most important first-generation modernists, reflects this greater understanding. The careers of the artists in the Shein Collection attest to a predilection, integral to the modernist enterprise, to break free from personal and national identity and their attendant psychological and geographical bounds to, in the American poet Ezra Pound’s epochal phrase, “make it new.” Before the 1913 Armory Show, Gertrude and Leo Stein in Paris and Alfred Stieglitz in New York created a dynamic transatlantic forum for artists such as Patrick Henry Bruce, Marsden Hartley, Stanton Macdonald-Wright, John Marin, Alfred Maurer, and Max Weber, as well as for the great European innovators Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso. After the Armory Show, largely orchestrated by Arthur B. Davies and a landmark in the history of modernism, Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell issued their synchromist manifesto on color painting and executed works of great chromatic complexity, while Hartley and Joseph Stella developed their singular styles, and Weber advanced his cubist practice. In 1915 Marcel Duchamp arrived in New York, where, inspired by the commercial and technological culture of the city, undertook variations on his revolutionary idea of the “readymade.” Duchamp’s brilliance soon inspired such precocious artists as Charles Demuth, Man Ray, Morton Schamberg, and Charles Sheeler, and was seminal to the formulation of American precisionism. In the 1920s, Marin, Arthur Dove, and Georgia O’Keeffe, prominent members of the Stieglitz group and well versed in the lessons of European modernism, pursued a refined, nature-based abstraction that Stieglitz promoted as distinctively American. At the same time Bruce and John Storrs developed their own mature modernist styles in France. |

|||

|

|

|||

Auto Tower, Industrial Forms, ca. 1922 Cast concrete, painted National Gallery of Art, Washington; gift and Promised Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein This sculpture tower, and another nearly identical example in the collection, incorporates the long body of a contemporary luxury touring car turned on its end, transforming a functional, industrial form into an architectural adornment or monument — a totem to American technology. Storrs, a Chicago native and the son of an architect, was knowledgeable about modernist buildings and here embraces the hallmarks of the art deco style: elegant geometry, graphic use of black, and fascination with technology. |

|||

|

|

|||

The Fisherman, 1919 Gouache on canvas Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein While living in Paris from 1905 to 1909, Weber befriended Pablo Picasso and witnessed firsthand the development of cubism. When the American artist returned home he brought with him the first painting by Picasso to enter the United States. Weber's own painting, too, adopted a cubist style, as seen in the fractured planes, masklike features, and subdued palette of The Fisherman. Too abstract to bear a true likeness, the portrait nevertheless resembles the artist, an avid fisherman, who smoked a pipe and wore vests and jackets much like those depicted here. |

|||

|

|

|||

Pre-War Pageant, 1913 Oil on canvas, 39-1/2 x 31-7/8 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein Painted in 1913, Pre-War Pageant is among the first purely abstract paintings by an American artist. Hartley had sailed for Paris a year earlier and there became interested in spirituality and art theories, including those of Wassily Kandinsky, who believed in the triangle’s spiritual properties. In Berlin in 1913, Hartley began a military-inspired series to which Pre-War Pageant belongs. With its bold use of primary hues and simple geometric forms, Hartley’s canvas pulsates with energy that spills beyond the canvas onto the frame. While in Europe during the teens Hartley maintained his ties to New York, sending pictures back to Alfred Stieglitz to exhibit at his intimate 291 Gallery. Recalling the effect of a Hartley exhibition in 1916, Georgia O’Keeffe remarked it was “like a brass band in a small closet.” |

|||

|

|

|||

Still-Life Synchromy, 1917 Oil on canvas, 22-1/8 x 30 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein In 1913 Macdonald-Wright, a young American artist living in Paris, boldly declared a new artistic style, which he (along with fellow American Morgan Russell) called Synchromism. Abstract, colorful, and rhythmic, the style found parallels with music. In the artist’s words, “I strive to divest my art of all anecdote and illustration and to purify it to the point where the emotions of the spectator will be wholly aesthetic, as when listening to good music.” Still-Life Synchromy was painted in 1917, after Macdonald-Wright had returned to the States. Its fractured composition disguises subject matter, though careful inspection reveals a pitcher on the right, an apple that seems to float above, and perhaps a figure in the background. |

|||

|

|

|||

Painting (Still Life), ca. 1919 Oil and pencil on canvas, 23-1/2 x 36-7/8 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein Living in Paris from 1904 to 1936, Bruce associated with the French avant-garde. He was close to Henri Matisse, and in 1908 became a founding member of Matisse’s art academy in Paris. Like the French painter, Bruce afforded color an essential role in his art, but he was also drawn to the still-life paintings of Paul Cézanne, which reduce natural forms to their underlying geometric structure. In this painting we detect a pair of cylindrical glasses and stacked rounds of cheese atop a skewed tabletop. Some of the tabletop forms may represent pieces of wood from antique furniture that Bruce, who was also an antiques dealer, would have possessed. |

|||

|

|

|||

End of the Parade: Coatesville, Pa., 1920 Tempera and pencil on board, 19-7/8 x 15-3/4 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein Demuth fused industrial style and subject matter, depicting the Lukens Steel complex with clear-cut lines and contained color—a style known as precisionism. The smokestacks and buildings are as crisply rendered as an architectural drawing, and even the billows of smoke are carefully delineated. Demuth’s painting, however, does not faithfully document the Lukens factory; one building is fancifully composed of stacked trapezoids, and rays of steely gray shoot across the sky in a decorative arrangement. Critics admired Demuth’s ability to find beauty in industrialized America. As Henry McBride noted, “He makes of it a thing that seems to glorify a subject that the rest of us have been taught to consider ugly.” |

|||

|

|

|||

Fresh Widow, 1964 edition (based on 1920 original) Painted wood frame and eight glass panels covered with black leather, 30-1/2 x 17-11?16 inches National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein Describing the manufacture of this sculpture, Duchamp said, “This small model of a French window was made by a carpenter in New York in 1920. To complete it I replaced the glass panes by panes made of leather, which I insisted should be shined everyday like shoes. French Window was called Fresh Widow, an obvious enough pun.” Indeed, the pun would have been especially pertinent in 1920, in the immediate aftermath of World War I. Signed by Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rose Sélavy (a pun on eros c’est la vie, or “eros, that’s life”), Fresh Widow offers a critique of how art traditionally operates. For instance, by covering the window panes with black leather Duchamp contradicts the basic notion that a painting should operate as a window into another world—an idea broadly accepted since the Renaissance. |

|||

|

|

|||

Dark Iris No. 2, 1927 Oil on canvas, 32 x 21 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein In warm weather, O’Keeffe left New York City for the more peaceful surroundings of Lake George in upstate New York, where she stayed with Alfred Stieglitz at his family’s summer home. The natural environs of the retreat provided both artists with rich subject matter. In Dark Iris No. 2, O’Keeffe plunges deep into the center of a black iris, presenting such an unusual and narrow focus that the painting verges on abstraction. The flower also may be seen as embodying sexual imagery, clouds, or even (turned on its side) the Lake George mountains and water. O’Keeffe alluded to the transformational power of art when she said, “When you take a flower in your hand and really look at it, it’s your world for the moment. I want to give that world to someone else.” |

|||

|

|

|||

Sunrise I, 1936 Wax emulsion on canvas, 25 x 35 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein In 1912 Alfred Stieglitz mounted a one-man exhibition of Dove’s work at his gallery 291—the first public exhibition of abstract art by an American. Dove’s abstractions were often rooted in nature and became increasingly bold in the latter part of his career, as seen in Sunrise I. Painted at his family’s property in western New York, the sunlike orb appears to glow over a horizon, yet the accompanying forms preclude such a literal reading. Some have seen this as a depiction of the moment of creation; it may hint at the artist’s interest in theosophy, which finds unity in all nature. |

|||

|

|

|||

Legend, 1916 Oil on canvas, 52 x 36 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein In the years leading up to his departure for Paris in 1921, Man Ray was an active participant in the New York salon of Walter and Louise Arensberg, and, along with Marcel Duchamp, a founding member of the Societé Anonyme and a key figure in the development of New York Dada. In Legend, Man Ray experiments with illusions of depth and flatness. He suggests the broad patches of color are like the sections of an umbrella, “where one takes off the tip and…turns it around on its curve,” rendering three dimensions as two. The emphasis on two-dimensional surfaces is further evident in the label or legend at the bottom center of the canvas that, in a form of wordplay, simultaneously refers to its own function and titles the work. |

|||

|

|

|||

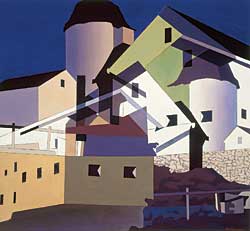

Composition around White, 1959 Oil on canvas, 30 x 33 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein Sheeler’s works, with their particular blend of quintessentially American subjects and modern style, often were described as both familiar and abstract. That is especially true in this depiction of a New England barn—his last variation on a theme that had occupied him for decades. The composition, rendered with broad, flat application of color, is based on photomontages the artist made of barns in which he layered negatives to create complex arrangements of superimposed architectural forms. |

|||

|

|

|||

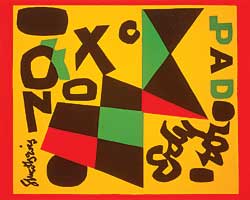

Unfinished Business, 1962 Oil on canvas, 36 x 45 inches Collection of Deborah and Ed Shein When the Philadelphia-born Davis exhibited at the Armory Show in 1913 he was one of the youngest participants. Beginning in the 1920s he brought the graphic sensibility and restricted palette of commercial advertising into his art. These qualities are evident in one of the artist’s last paintings, Unfinished Business, in which Davis engages viewers in a bit of visual wordplay. An assortment of Xs and Os suggests tic-tac-toe players that have slipped off their grid. In the lower right quadrant, “Edy” is rendered in script, and along the right edge “PAD” is printed. The former is likely a variation of the sequence “Ideas—Eyedas—Eyedeas” that Davis recorded in one of his sketchbooks, also known as sketchpads or “pads.” Combined with the letters “NO” at left we may surmise that Davis was referring to the American poet William Carlos Williams’ famous axiom, “No ideas but in things.” |

|||

|

|

|||

| Presented here are details of a selection from the twenty works on exhibit in American Modernism: The Shein Collection, on view through January 3, 2011, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. American Modernism was organized by Charles Brock and Nancy Anderson, with Harry Cooper. For further information call 202.737.4215 or visit www.nga.gov. |

|||

|

|

|||

| Charles Brock is associate curator of American and British Paintings, Nancy Anderson is curator and head of the department of American and British Paintings, and Harry Cooper is curator and head of the department of Modern and Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. |

|

|