|

|

|

|

|

BY HENRY ADAMS

|

|

|

|

N.C. (Newell Convers) Wyeth (1882–1945)

The Little Posse Started Out on its Journey, the Wiry Marshal First, 1907

Oil on canvas, 30 x 20 inches

Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum,

Gift of Mrs. H.S. (Johnie) Griffin |

The saga of the Wyeth family stands out as unique in the history of American art. No other family has produced nationally significant painters in three successive generations. The work of all three painters of the Wyeth family is now featured in a major exhibition at the Tyler Museum of Art in Tyler, Texas—the first museum exhibition in Texas since 1987 to feature the three generations of Wyeths and only includes works drawn from private and public collections within the state.

N. C. Wyeth

Newell Convers Wyeth (1882–1945), the first member of the Wyeth family to become a famous artist, was born in 1882 in Needham, Massachusetts. While he took drawing lessons and collected illustrated magazines (particularly drawn to the dramatic western scenes of Frederic Remington), perhaps his greatest education came from the chores he did on the family farm, which gave him a rich sense of the nature of physical movement and work.

Despite a thorough schooling with a long list of anatomy teachers, illustrators, and landscapists, it was not until he went to study with the famous illustrator Howard Pyle that he was lifted from a plodding student to one of the country’s most extraordinary illustrators. Pyle unleashed Wyeth’s imagination and taught him to “live in the picture,” thinking of the dramatic significance of every figure and element.

|

|

|

|

N.C. (Newell Convers) Wyeth (1882–1945)

The Boyhood of C.A. Lindbergh Yields

Many Clues to His Personality as a Man, 1931

Oil on canvas, 25¼ x 30¼ inches

Collection of Chip Hosek, Pearland

|

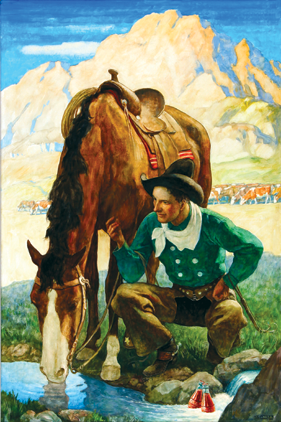

In September 1904, on Pyle’s insistence, N. C. Wyeth headed west to live the life of a cowboy in Colorado and New Mexico. While it lasted only thirty days, somehow in that time he was able to work as a cowboy on a round-up, sleep under the stars, get robbed, work as a mail rider, visit Indian pueblos, and collect quantities of Indian artifacts and cowboy costumes.

Over the next five years he specialized in western scenes—not only book and magazine illustrations, but advertisements for companies such as Quaker Oats, producing no fewer than two a month. This work provided a substantial income. Scribner’s published seven of his western pictures in an article he wrote himself, “A Day with the Round-Up,” that included photographs of himself in western gear and turned him into a national celebrity. At the time he was only twenty-three. Five years later, in 1911, publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons asked him to illustrate an “elaborate edition” of Stevenson’s Treasure Island for the sizeable fee of $2,500, enough to purchase a parcel of land and build a home.

|

|

|

|

N.C. (Newell Convers) Wyeth (1882–1945)

Cowboy Watering his Horse, ca. 1937

Oil on hardboard (Renaissance panel),

36 x 24 inches

Museum of Texas Tech University |

Wyeth completed the illustrations for Treasure Island just before his twenty-ninth birthday. In many ways the series is his masterwork; it certainly strikes a new note in American illustration. In a stroke, Wyeth made Pyle’s genteel Victorian style obsolete. There was a physicality and immediacy to his work that was new.

For a generation of viewers, N. C. Wyeth’s drawings became the real story of what was happening in the books he illustrated, with the result that when Hollywood movies were made of the same texts, scenes were staged to look exactly like a specific illustration. To depart from the look of Wyeth’s illustrations would have been viewed by Americans of the time as a departure from truth.

Andrew Wyeth

Soon after settling in Chadds Ford, N. C. Wyeth started a family. Andrew (1917–2009), the youngest child, was born on on the hundredth anniversary of the birth of the unconventional nature writer and philosopher Henry David Thoreau, one of N. C.’s heroes.

Andrew was the most painfully sensitive of the children. Born with a faulty hip that made him walk with his feet splayed out like a duck, he was frequently ill and had bouts of anemia, double hernias, whooping cough, and a chronic sinus condition that required medicine-soaked swabs up his nose. Considered too delicate to go to school, he was educated haphazardly at home by a succession of tutors and spent much of his time making drawings, playing with his collection of toy soldiers—by the time of his death he had gathered well over two thousand—and roaming the woods and fields with his friends, wearing the costumes his father used as an illustrator.

|

|

|

Andrew Newell Wyeth (1917–2009)

Rattler, 1960

Watercolor on paper, 29¾ x 20½ inches

Private Collection, Dallas

© Andrew Wyeth

|

|

Andrew Wyeth’s first notable paintings, a reaction against his father’s rigorously academic training, were watercolors of Maine that reflect the influence of Winslow Homer. Wyeth began producing them in the summer of 1936, when he was just nineteen. Fluid and splashy, they were dashed off rapidly—sometimes seven or eight in a single day. In October 1937 he held his first one-man show at the Macbeth Gallery in New York, and while it was the heart of the Great Depression, crowds packed in and the show sold out on the second day. At the age of just twenty, Andrew Wyeth had become an art world celebrity. Not long after, he was on the cover of American Artist magazine.

|

|

|

Andrew Newell Wyeth (1917–2009)

Henriette, 1967

Drybrush and tempera,

21½ x 28½ inches

San Antonio Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Robert

J. Kleberg, Jr. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation

© Andrew Wyeth

|

|

But even as he achieved art world stardom, Andrew was beginning to feel that his work was too facile and that illustration was too limiting. He turned to the laborious, exacting Renaissance method of tempera—egg yolk mixed with dry pigment. While his wife Betsy, supported this direction, his father was not encouraging, and neither was Robert Macbeth. In 1942, when Wyeth produced a large tempera of two buzzards soaring over Chadds Ford, he was so discouraged by his father’s response that he put the painting down in the basement, where his children used it as a support for their train set and nailed railroad track to the back.

In the summer of 1948, Andrew began a painting of a crippled woman, Christina Olsen, painfully using her arms to pull herself up a seemingly endless sloping hillside. For months Wyeth worked on nothing but the grass; then, much more quickly, he precisely delineated the buildings at the top of the hill. Finally, he came to the figure itself. Her body is turned away from us so that we get to know her simply through the twist of her torso, the clench of her right fist, the tension of her right arm and the slight disarray of her thick, dark, carefully pulled-back hair. Against the subdued tone of the brown grass the pink of her dress feels almost explosive. Wyeth recalled that after sketching the figure, “I put this pink tone on her shoulder —and it almost blew me across the room.” 1

|

|

|

|

James Browning Wyeth (b. 1946)

The Monhegan Post Office, 1976

Watercolor on paper, 21½ x 29 inches

Collection of Chip Hosek, Pearland |

When he was done, Wyeth hung the painting over the sofa in his living room. Visitors hardly glanced at it. In October, when he shipped the painting to his New York City gallery he commented to his wife, “This picture is a complete flat tire.” 2

He could not have been more wrong. Within days whispers about a remarkable painting were circulating in New York. Powerful figures of finance and the art world quietly dropped by the gallery, and within weeks Christina’s World had been purchased by the Museum of Modern Art. When it was hung there, thousands of visitors related to the painting in a personal way, and somewhat to the embarrassment of the curators who favored European modern art, it became the most popular work in the museum. Within a decade the museum had pocketed reproduction fees amounting to hundreds of times the sum they had paid to acquire the picture.

Just thirty-one years old, Wyeth had accomplished something that eludes most painters. He had created an iconic work, an emotional and cultural reference point for millions of Americans.

|

|

|

|

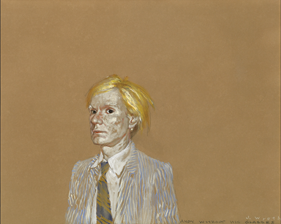

James Browning Wyeth (b. 1946)

Andy Without His Glasses, 1977/2008

Combined mediums on toned paper board,

16 x 20 inches

Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Meredith

Long, Houston

|

Jamie Wyeth

James Browning Wyeth was born in 1946, the second of Andrew and Betsy Wyeth’s sons.3 He decided at an early age that he wanted to be an artist. Why this was the case is somewhat mysterious, since his older brother never felt any such inclination. He himself believes that his decision was greatly influenced by his exposure to his grandfather’s musty studio. Many of Jamie’s early paintings focus with relentless exactitude on the appearance of simple objects: bales of hay, a bell set against the ocean, lawn chairs, neatly stacked firewood, sacks of grain.

In 1966, when he turned twenty, he staged a one-man show at Knoedler Galleries, perhaps the most distinguished New York gallery of the period, one that chiefly handled blue-chip paintings by Old Masters. Lincoln Kirstein wrote an effusively celebratory essay for the catalogue in which he declared that Jamie was the greatest American portraitist since John Singer Sargent. Most of the paintings sold. But the show was also the subject of a vituperative review by Hilton Kramer, art critic for the New York Times, who not only lambasted Jamie’s work but that of his father, arguing that the work of neither was worthy of even being called art.

|

|

|

|

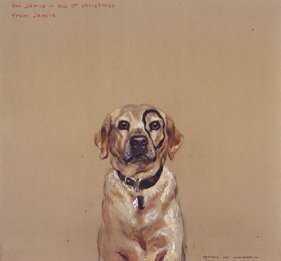

James Browning Wyeth (b. 1946)

Study for Kleberg, 1984

Combined mediums on cardboard,

15¼ x 14¾ inches

Private collection, San Antonio |

In 1967 Jamie married a beautiful heiress, Phyllis Mills, who had worked for the Kennedy family, and in the same year he received the commission to paint a posthumous portrait of John F. Kennedy. The finished painting, which showed Kennedy caught in a moment of private thought, looking very vulnerable, stirred up controversy and was the subject of a major story in Look Magazine.

Up to this time, with the exception of the Kennedy portrait, most of Jamie’s work had fit squarely into the Wyeth family tradition and focused on the people and things of familiar Wyeth stomping grounds—Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, and Cushing, Maine. Many of them looked a great deal like the work of his father. But at this point, Jamie’s work started to take on a somewhat different character, as Jamie became a fixture in the New York art scene that his father had assiduously avoided. What started all this was when Jamie agreed to paint Lincoln Kirstein’s portrait. As Jamie notes, “The New York thing was really due to Lincoln Kirstein.” 4

Through Kirstein, a founder of the American Ballet, Jamie became immersed in the world of ballet, and this was what drew him to his series of paintings and drawings of Rudolf Nureyev, which became the center of his life for the next several years. It seems to have been Nureyev who brought Jamie Wyeth into the circle of Andy Warhol. For Jamie, Warhol was fascinating because he provided a new model for what being an artist was all about.

Yet while pursuing these New York paintings, Jamie continued to produce paintings of subjects more typical of the Wyeth tradition, such as animals and landscapes, solidly based on close observation of his surroundings in Maine and at Chadds Ford. But his handling of these themes began to develop a slightly more eerie, unsettling quality, in some way related to his engagement with modern art.

|

|

|

|

James Browning Wyeth (b. 1946)

Another Daydream, Monhegan, 2006

Combined mediums on toned rag board,

18 x 24 inches

Collection of Tina and Joe Pyne, Houston |

Animals were the subject of some of Jamie’s earliest paintings, and he has returned again and again to painting them. To paint animals Jamie has pursued a process very close to the “method acting” he employs with his human subjects. He has lived intimately with animals, keeping a wolf in his living room, studying sharks in a specially constructed tank, working in a studio in his barn with raccoons scrambling on the ceiling over his head. Many of his most remarkable paintings have portrayed birds, such as ravens and seagulls, focusing on their savagery as well as their beauty.

In the American art world the Wyeth family occupies a prominent but uneasy place. They have each achieved extraordinary success, and at the same time have often been regarded as not quite “real artists”; N. C. Wyeth because he was “just an illustrator”; Andrew Wyeth because he never played the social games of the New York art world and never joined the march to abstraction; Jamie for his interest in making handmade paintings at a time when the art world is more interested in installations and conceptual art, and yet at the same time the brashly modern qualities of his work place him in a different camp than those who create nostalgic replicas of nineteenth-century styles. Perhaps Jamie’s remark that his father was really “an outsider artist” comes closest to the mark. For three generations, the Wyeth’s have been outsiders; yet curiously, they have all managed to achieve great popular success while breaking so many of the usual rules.

|

|

|

|

|

Henry Adams is a Professor of American Art at Case Western Reserve University.

1. Richard Meryman, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life (Harper Collins, New York, 1996), 21.

2. Meryman, 22.

3. Meryman, 136.

4. Jamie Wyeth interview 2011.

The Wyeths Across Texas is on view at the Tyler Museum of Art, Tyler, Texas, through December 9, 2012. The exhibition will travel to the El Paso Museum of Art. A catalogue accompanies the exhibition.

|

|