Washington, D.C. Stoneware

|

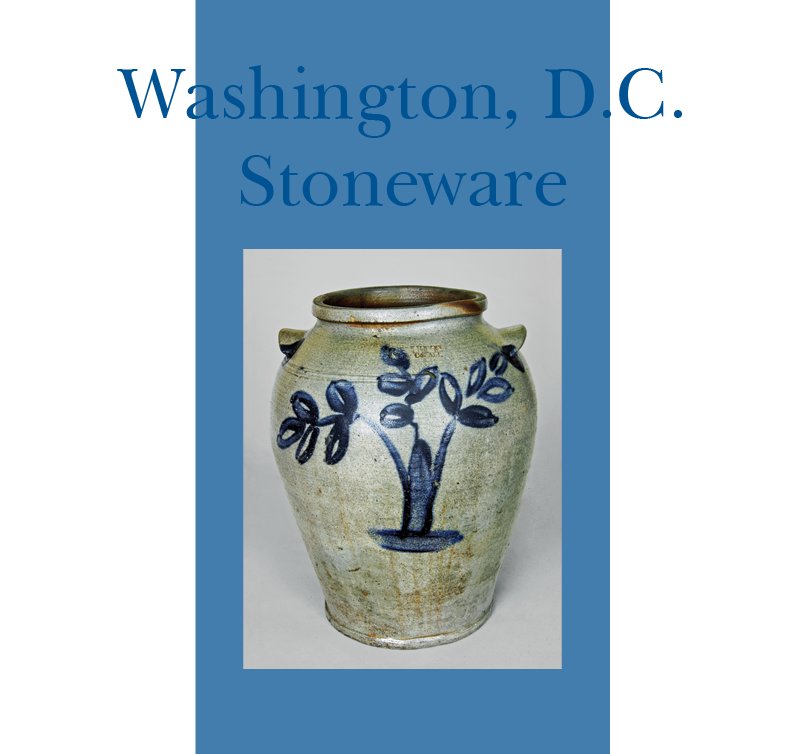

| Fig. 1: Jar made at Richard Butt's pottery in Olney, MD (ca. 1826–ca. 1831), circa 1830. Impressed "R. BUTT / Monty Co. Md." Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12¼ in. This is the only known vessel bearing the mark "R. BUTT / Monty Co. Md." Courtesy of a private collection. |

On the night of August 8, 1850, abolitionist William Chaplin attempted to carry out a plan he had successfully executed many times before—ferrying runaway slaves out of the District of Columbia, through Maryland, to freedom. The slaves in question belonged to Georgia representatives Robert Toombs, later vice president of the Confederacy, and Andrew Stephens, later Confederate secretary of state and army general. As Chaplin and the two men tried to cross into Montgomery County, local authorities descended on their carriage. Chaplin and the slaves opened fire, but managed little injury to the officers, the greatest wound falling to Richard Butt, a local bureaucrat who took a bullet in the arm. The Chaplin affair made national news; the abolitionist's bullet-ridden carriage was put on display and viewed by thousands on a street corner in Washington, and stories ran in papers as far away as Wisconsin. None, however, mentioned that Richard Butt had, some years earlier, been the proprietor of Washington's most prolific stoneware manufactory.

| |

| Fig. 2 & 2a: Jar with elaborate slip-trailed decoration, probably made at Richard Butt's Olney, MD pottery (ca. 1826–ca. 1831), circa 1828. Inscribed under each handle "R. Butt." Salt-glazed stoneware, H. 10 in. Courtesy of a private collection. |

Richard Butt (ca. 1793–1865) was probably born in Montgomery County, Maryland. He married his wife, Sarah Ann, in 1814, and by 1822 was serving as deputy sheriff in the county, running for sheriff two years later. He clearly had an entrepreneurial spirit, acquiring the earthenware pottery of Whitson Canby in Mechanicsville (now Olney) in Montgomery County, sometime circa 1826. Often referred to as the "Fair-Hill Manufactory," after a nearby manor home of the same name, under Butt's ownership the shop expanded out of low-fired, lead-glazed earthenware and began producing high-fired, salt-glazed stoneware. The area's stoneware industry was already burgeoning in Alexandria (then part of the District of Columbia) and Baltimore when Butt's pottery ventured into the business. A single extant piece of stoneware bears the mark of Butt's Montgomery County pottery: "R. BUTT/Monty Co. Md." (Fig. 1). Another jar inscribed simply "R. Butt" in cobalt slip under each handle was also probably made at this shop and most likely predates the marked example (Figs. 2, 2a). The profuse "slip-trailed" decoration—achieved by finely applying the cobalt slip through a quill or other nozzle—is seen on Baltimore wares of the time period, and on later Alexandria wares.

| |

| Fig. 3: Section of Map of Washington City… by A. Boschke, 1857, showing detail of the 8th and I Street Manufactory and its location relative to White House and Capitol. This map featured outlines of most, if not all, of the buildings in Washington, allowing us to ascertain the layout of the property at the time. The circular building off the street may have been the kiln. |

Butt maintained ownership of his Mechanicsville pottery until at least 1831. Perhaps hoping to capitalize on what was already a lucrative market in the nation's capital, by 1834 he opened for business at the southwest corner of Eighth and I Streets NW in Washington, D.C.—developing an area that would come to be known as "Potters' Kiln Square," later remembered as "Generally Shrouded In Smoke" (Fig. 3).

The first known stoneware pottery in what is today considered the District of Columbia was probably founded in the late 1810s by James Miller (ca. 1779–ca. 1850), a potter who had worked in Alexandria around the turn of the nineteenth century. Miller apparently set up shop on High Street (now Wisconsin Avenue) in Georgetown, but had returned to Alexandria by the mid-1820s.

Concurrent with his ownership of the pottery, Butt was overseer of the city's "asylum for the paupers of the District," which was "also used as a work-house for persons convicted of minor offences (sic)," a job he began on November 1, 1832. Clearly not a potter himself, Butt may have occasionally employed menial labor in the form of inmates from the asylum. His master potter during this early time period—and, probably, throughout much of his proprietorship—was apparently one John Walker (ca.1805–ca.1880), who is listed in the 1834 city directory as living by the pottery on I Street. Walker was born in England and emigrated to the United States with his wife, Sarah, and small daughter, Anna, sometime circa 1830.

| |

| Fig. 4: Jar made by John Walker (w. in D.C. ca.1830–ca.1838) in the District of Columbia. Impressed "JOHN WALKER." Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10½ in. The circle with dangling foliate decoration is otherwise unique to Alexandria stoneware. Courtesy of a private collection. |

Fully trained, Walker had obviously learned his trade in England. Rare, surviving vessels stamped with the mark "JOHN WALKER" and "JOHN WALKER / D.C." show us that the Englishman easily accustomed himself to producing pottery in the style of his new surroundings (see Figs. 4, 5). The designs seen on Walker pieces are often highly derivative of those used in Alexandria (and also Baltimore), and his forms resemble closely those made in both cities. Walker's hand is seen in the decorations of many extant Butt vessels. For instance, the two-gallon Walker jar in figure 5 and the six-gallon Butt jar in figure 7 were quite clearly decorated by the same person.

Two different marks are found on extant pieces of Butt's pottery: "R. BUTT / W" and "R. BUTT / W City D C" (Figs. 6, 7). The "W" pieces are apparently earlier than the "W. City" ones, and variations in typefaces and positioning of type are seen among examples. The evidence suggests that John Walker oversaw Butt's shop from the outset and that he initially began stamping the work with the abbreviated mark before moving on to the "W. City" stamp some years later. It is unclear where, or when, the "JOHN WALKER" pieces were made, but they seem to predate Walker's work for Butt; if so, Walker's time at the 8th and I Street Manufactory may have preceded Butt's proprietorship.

| |

| Fig. 5: Two-gallon jar made by John Walker (w. in D.C. ca. 1830–ca. 1838), District of Columbia. Impressed "JOHN WALKER." Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 13 in. Courtesy of a private collection. |

A career John Walker undertook simultaneously with his potting enterprises makes him unique—he was also a physician. By about 1840, Dr. Walker had moved to Ohio, where, by 1850, he was clearly working with the renowned stoneware potter Cornwall Kirkpatrick, of Anna Pottery fame, and then in Point Pleasant on the Ohio River. Also around that time, Walker's daughter, Anna, married a Pennsylvania-born potter named Lewis Mangan, and by 1860 Dr. Walker and his son-in-law were making pottery in the Frankfort, Kentucky, area. In 1880, the potter-doctor was still alive, listed in that year's census as a seventy-four-year-old retiree living with the family of his daughter and son-in-law.

Though Walker's immediate successor at Butt's pottery is unknown, two distinct design styles can be noted in the "R. BUTT" ware. The first, a variation on Alexandria and Baltimore stoneware, was probably produced under Walker; the second was rendered by a very different hand, possibly that of his successor (Fig. 8), most likely German immigrant potter Joseph Straub (ca. 1800–ca. 1868). Straub had arrived in the District circa 1834 and would open his own pottery by 1843 on the east side of 7th Street between K and L Streets NW. However, to view Butt's establishment as primarily operated by two men is probably too simplistic. Many potters may have made their way through Butt's pottery, and more than two or three may have run it.

|

| Fig. 6: One-gallon jars made at Richard Butt's pottery in Washington, D.C. (ca. 1830–ca. 1845), circa 1834. Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Impressed "R. BTT / W"; H. 10 ½ in. Right: Impressed "R. BUTT / W"; H. 10 3/4 in. The "R. BTT" example is the only one known marked without the U, demonstrating that the stamp was probably fashioned using moveable metal type. Slight typographical variations in the apparently later W. City mark are also seen. Courtesy of a private collection. |

|  | |

| Left: Fig. 7: Six-gallon jar made at Richard Butt's pottery in Washington, D.C. (ca. 1830–ca. 1845), circa 1838. Impressed "R BUTT / W City DC." Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 in. This Butt jar was clearly decorated by the same hand as that seen on the Walker jar in Figure 5. Courtesy of a private collection. Right: Fig. 8: Three-gallon jar made at Richard Butt's pottery in Washington, D.C. (ca. 1830–ca. 1845), circa 1840. Impressed "R. BUTT / W. City. D C." Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14½ in. The decorator's hand on this vessel is clearly different than that seen on the bulk of stoneware with Butt's mark. Courtesy of a private collection. | ||

|

| Fig. 9: Bowls excavated across the street from Enoch Burnett's Washington, D.C. pottery (ca. 1846–ca. 1879). Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: Partially-reconstructed handled bowl; H. 6 in. Center: Reconstructed fragment of bowl; H. 6 3/4 in. Right: Reconstructed fragment of handled bowl; H. 6½ in. Photographs by Brandt Zipp & Mark Zipp. |

|

| Fig. 10: Vessels made at Enoch Burnett's Washington, D.C. pottery (ca. 1846–ca. 1879). Salt-glazed stoneware. Left: One-and-one-half-gallon jar; H. 11 3/4 in. Center: Pitcher; H. 10 3/4 in. Right: Bowl; H. 5 5/8 in. Usually referred to as a "milk pan," this take on the form is taller and more slender than most seen in American stoneware production. Courtesy of a private collection. |

Butt apparently sold his business by 1846 to Enoch Burnett, who continued to operate the pottery well after the Civil War. He continued to serve as intendant of Washington Asylum until 1847, when he was removed for what seem to have been mostly false accusations of malfeasance. By 1850, he was probably at least loosely associated with local law enforcement, based on his involvement in the Chaplin affair. Not only interested in returning runaway slaves to their masters, Butt was himself a slave owner, and probably employed slave labor at the manufactory, as did his successor, who owned at least one slave while living in the District. Somewhat ironically, in 1863, President Lincoln appointed Butt commissioner of the Metropolitan Police of the District of Columbia. He died two years later, still holding that position.

| |

| Fig. 11: Detail of maker's marks seen on Washington, D.C. stoneware, ca. 1830–ca. 1890. With the exception of slight variations, these are the only marks known to have been used in Washington during this period. |

It would be hard to overstate the importance of Butt's successor, Enoch Burnett (1796–ca. 1879), to the history of Mid-Atlantic stoneware manufacture. Born on December 2, 1796, Burnett was an orphan when he was bound as an apprentice to Baltimore potter Thomas Amoss at the age of sixteen in 1813. On July 27, 1824, he married Margaret Remmey, daughter of Henry Remmey Sr. (ca. 1760–1843), becoming part of America's most prolific family of stoneware potters. In 1827, he and his brother-in-law, Henry Harrison Remmey, purchased Branch Green's local stoneware pottery in Philadelphia. Four years later, Burnett sold his share to Remmey, who, along with his family, would carry the business into the twentieth century, their pottery becoming a titan of the industry.

By the late 1830s, Burnett found employment at the likewise prolific pottery of Maulden Perine (1799–1865) in west Baltimore. He continued to work there until at least circa 1842, before taking the reigns of the 8th and I Street Manufactory, where he would pot for more than three decades.

Burnett chose, apparently, not to identify his wares with a mark—a decision shared by most Baltimore potters of the period, and one that relegated his work, and Burnett himself, to historical obscurity. An archaeological dig begun in 1989, however, near the southeast corner of Eighth and I Streets NW, just across the street from the pottery, unearthed shards and partially reconstructed vessels that display the hurried swags and telltale flower head now identified as a signature of Burnett's work (Fig. 9). Extant intact vessels now attributed to the potter reveal a floral sprig decoration unique to him (Fig. 10).

Enoch Burnett lived beyond the age of eighty, passing away sometime circa 1879. The manufactory of Richard Butt and Enoch Burnett provided necessary housewares for people ranging from affluent politicians and government figures to laborers and slaves. Other stoneware potters, most notably Paul Hiser (1824–ca. 1900) and his family, and William H. Ernest (1859–ca. 1925)—the only other Washington potters known to mark their work—carried the torch, but embraced the trend toward mass production at the time. The Hisers' work was rarely decorated, and Ernest's apparently never was. Although the wheel of the Washington potters ceased long ago, the pots remain as small monuments of their time, their city, and the men who made them (Fig. 11).

1. Pottery Folder, Vertical File, Montgomery County Historical Society Library; and Healan Barlow and Kristine Stevens, Olney: Echoes of the Past (Family Line Publications, Westminster, Maryland, 1993), 20–22. The research notes of Mike Dwyer, Historian of The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, and the MCHS's files in general, were invaluable in researching Butt's Olney years.

2. "Montgomery County Tax Records, 1831," 5th District; and 1834 Washington, D.C. Directory, 4; and Washington The Evening Star, September 16, 1906, 11.

3. Brandt Zipp and Mark Zipp, "James Miller: Lost Potter of Alexandria, Virginia," Ceramics in America (2004): 253–261; and Georgetown National Messenger, April 24, 1820, 3. The first known pottery within the limits of Washington was operated circa 1827 by "M. Swan," almost certainly a relative of prolific Alexandria potter John Swann; Swan's pottery was located on 7th between L and M Streets SE near the Navy Yard, but whether he produced stoneware is unknown.

4. Joseph West Moore, Picturesque Washington: Pen and Pencil Sketches … (Providence, R.I.: J. A. and R. A. Reid, 1884), 262; and The Baltimore Sun, February 20, 1847, 1.

5. 1834 Washington, D.C. Directory, 59; 1850 Federal Census, Ohio, Clermont County, Monroe Township, 5; and 1850 Federal Census, Kentucky, Franklin County, District No. 1, 49.

6. Ermina Jett Darnell, Filling the Chinks (Frankfort, Ky.: Roberts Print. Co.,1966), 83.

7. 1840 Federal Census, Washington, D.C., 53; and 1850 Federal Census, Washington, D.C. Ward 3, 205; and 1843 Washington, D.C. Directory, 82. The Joseph "Straub" or "Shrub" enumerated next to Butt in the 1840 census is almost certainly However, according to The Washington Evening Star, May 17, 1908, 3,Straub had already purchased his 7th Street pottery by 1837.

8. 1846 Washington, D.C. Directory, 29.

9. The Baltimore Sun, February 3, 1847; February 18, 1847; and February 20, 1847.

10. 1860 Federal Census Slave Schedule, Washington, D.C., 49; and National Intelligencer Newspaper Abstracts, Special Edition: The Civil War Years ... Vol. 1 (Heritage Books, Westminster, Maryland, 2001), 328. 1850 Federal Census Slave Schedule, Washington, D.C. Ward 3, 667.

11. Journal of the Executive Proceedings of the Senate of the United States of America... (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1887), V. XIII: 142. In the 1860 census, Butt is listed as a "Gardener + Toll-Gatherer."

12. John N. Pearce, "The Early Baltimore Potters and Their Wares, 1763-1850," MA thesis, University of Delaware (1959), 94. Pearce isn't sure that Burnett was born in 1796, but a separate genealogical source found on familysearch.org provides the same 1796 date.

13. Baltimore American, August 4, 1824.

14. Susan H. Myers, Handcraft to Industry: Philadelphia Ceramics in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), 22–25.

15. Mark Walker and Liz Crowell, "Pottery From The Butt/Burnett Kiln, Washington, D.C." Paper presented at the Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology, Richmond, Va., January 1991.

16. I am grateful to Nancy Kassner, former state archaeologist at the D.C. Historic Preservation Office, for helping me track down, handle, and photograph the Burnett shards. I would also like to acknowledge my brother, Mark Zipp, who researched the Washington stoneware industry alongside me, and my brother, Luke Zipp, for his invaluable assistance with research and photography.

17. The Hisers' pottery was located on Wiltberger Street NW, and Ernest's on Georgia Avenue SE (now Potomac Ave.). See 1886 Washington, D.C. Directory, 114

Brandt Zipp is a partner in Crocker Farm, Inc., an antiques auction house specializing in American stoneware and redware pottery. He is currently authoring a book on Thomas Commeraw, the free African American potter of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Manhattan.

All photographs by Luke Zipp, except where noted.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2010 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|