California's William Keith Celebration and Neglect by Alfred C. Harrison, Jr

|

| Fig. 1: Keith Room, Hearst Art Gallery, Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif. |

by Alfred C. Harrison, Jr.

During his lifetime, landscape painter William Keith (1838–1911) had a reputation that spread widely across the country from his home base in San Francisco. Especially towards the end of his career in the early twentieth century, his works were sought after by major collectors in the East, as well as by Californians.

At the Panama Pacific International Exposition of 1915, four years after his death, Keith’s work was given a separate gallery—he was the only artist to receive such an honor. But as modernism drove nineteenth-century art into oblivion, not even Keith was spared. Keith was luckier than many other California artists of his time; he acquired a tireless advocate and biographer in the Swiss-born Christian Brother, Herman Emanuel Braeg, whose name in the church was Brother Cornelius. A professor of German literature and sacred studies at Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, half an hour east of San Francisco, Cornelius saw his first Keith paintings in naturalist John Muir’s house in 1908, which led to his obsessive quest for the facts of Keith’s life and for Keith paintings in private collections and public institutions throughout Northern California. In this crusade, he was helped by Keith’s widow, Mary McHenry Keith, and niece, Elizabeth Keith Pond, who assembled a multi-volume compendium of material—letters, newspaper reviews, catalogues of his exhibitions, etc., relating to Keith. The “Keith Miscellanea,” eventually found a home at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, while Cornelius’s biography, Keith, Old Master of California, was published in 1942.

|

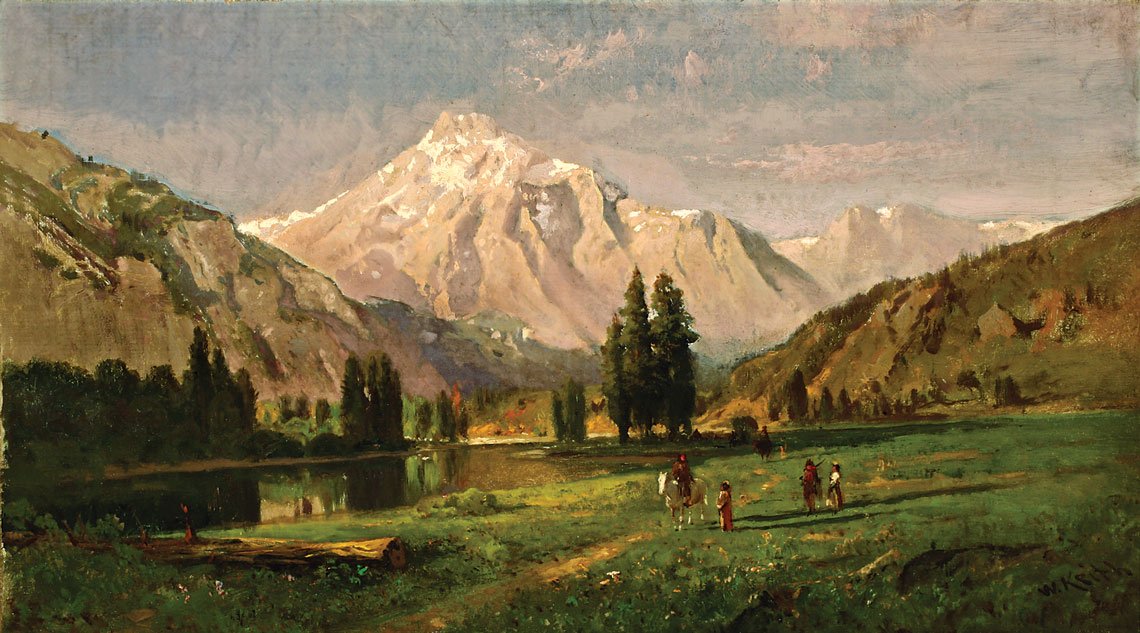

| Fig. 2: William Keith (1838–1911) Glacial Meadow and Lake, High Sierra (Tuolumne Meadows), 1870s Oil on canvas, 14-1/4 x 26 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Dr. William S. Porter |

|

| Fig. 3: William Keith (1838–1911) Dazzling Clouds, ca. 1890 Oil on canvas, 30 x 39-3/4 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Ina Brackenbury |

|

| Fig. 4: William Keith (1838–1911) Klamath Lake with Pelicans and Mount McLaughlin, ca. 1908 Oil on canvas, 22 x 32 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Averell Harriman |

Because Cornelius’ enthusiasm coincided with the period when interest in nineteenth-century California art was at its lowest ebb, many Keith paintings were donated to Saint Mary’s College, where in 1934, a gallery devoted to his work was established. Today Saint Mary’s owns 180 Keith paintings, and its Hearst Art Gallery maintains a permanent Keith Room (Fig. 1). This modest institution has also initiated exhibitions devoted to the art of Keith’s time, expanding our knowledge of and appreciation for this remarkable corner of California culture. This year, the one-hundredth anniversary of Keith’s death, a major retrospective exhibition of Keith paintings will be on view through December 18.

William Keith was born in Northwest Scotland. In 1850, at the age of twelve, he immigrated to New York with his mother and three sisters, his father having died before Keith was born. He learned the trade of wood engraving and found employment with Harper and Brothers. Nine years later Keith relocated to San Francisco. Acting on a long-time interest in becoming a painter, in 1863 Keith took a course in oil painting from Samuel Marsden Brookes (1816–1892); a year later Keith listed himself in the San Francisco Directory as an artist.

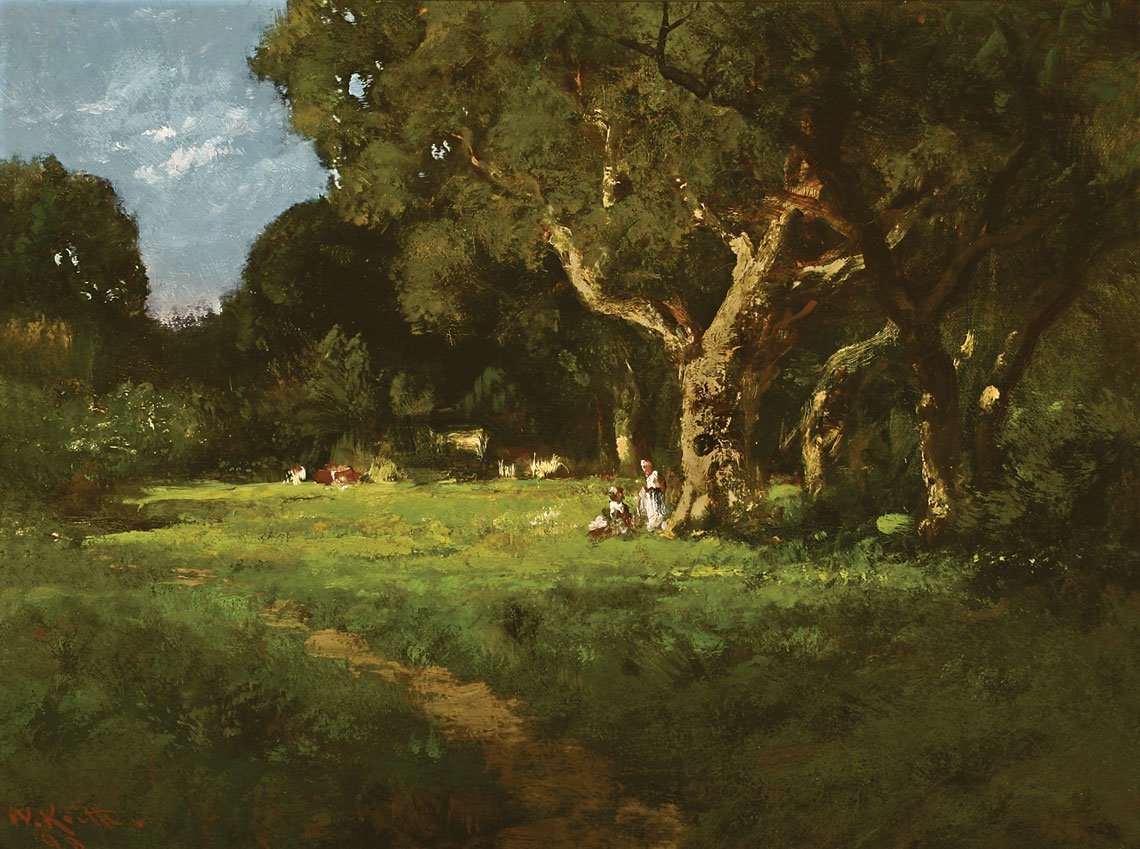

San Francisco was an active center for painting in the 1860s when Keith began his long career. During this time, New York’s Hudson River School way of painting was in the ascendancy, fading from fashion during the 1870s and forgotten by the first decade of the twentieth century with the introduction of the plein-air style. Through the years, Keith’s style moved from Hudson River School celebrations of mountain grandeur (Fig. 2), to moody, humble landscapes in the French Barbizon mode (Fig. 3). Keith was a successful practitioner of both styles of painting, but it was during his late career that he became recognized as one of America’s leading artists. Toward the very end of his life, he experimented with brighter paintings, somewhat influenced by the plein-air movement (Fig. 4), but his conviction that such works were unable to convey deep spiritual meaning limited his production in this style.

His early works of the 1860s earned him the funds for a trip abroad to study art in Düsseldorf and Paris. Returning from Europe in 1871, he set up a studio in Boston, and by the spring of 1872 was considered to be one of Boston’s leading painters. One Boston critic praised his “...rare power of perspective, which he produces by light and shadow and gradation of color.” Meanwhile, he sent two major works to the National Academy in New York, where they attracted a favorable article in the New York Times. That summer, upon his return to San Francisco, Keith’s paintings like Mount Tamalpais, Golden Morning (Fig. 5), were considered by critics there to be the equal of works by Thomas Hill (1829–1908) and Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), the latter in the middle of his three year sojourn as a resident San Francisco painter. For the rest of the decade, local art critics treated Keith as San Francisco’s leading artist.

|

| Fig. 5: William Keith (1838–1911) Mount Tamalpais, Golden Morning, 1872 Oil on canvas, 39-5/8 x 72-1/4 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Sidney L. Schwartz in honor of Garrett W. McEnerney |

|

| Fig. 6: William Keith (1838–1911) Russian River Panorama, 1876 Oil on canvas, 36 x 72 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Harmon Edwards |

Much of Keith’s critical acclaim during the 1870s was inspired by his large paintings of mountain subjects, which—as Keith well knew—were no longer fashionable on the East coast. Subjective mood paintings in the French Barbizon mode were all the rage. Keith was reminded of the truth of this situation when in November of 1878 he sent a group of mountain landscapes to Leavitt’s Art Gallery in New York. Clarence Cook, art critic of the New York Tribune, got right to the point: “These pictures are a forcible illustration of a popular error among us...that to have great painting, it is necessary to paint great things.” Increasingly, Keith either painted works that combined Hudson River School mountain subjects with Barbizon-influenced broadly painted foregrounds (Fig. 6), or mood pieces of generic California scenery directly in the Barbizon mode (Fig. 7). Not all his paintings in this style (Fig. 8) pleased San Francisco critics still enamored of grand subjects. One reviewer wrote: “It is a great mistake in Mr. Keith to suppose that the public taste will be satisfied with landscapes in which there is a yellow sunset, with...middle ground and foreground so vaguely painted that nothing can be seen distinctly save the sky.”

Keith’s reputation dwindled in the 1880s, as the San Francisco art world experienced hard times caused in part by the disappearance of wealthy patrons who had profited from the Comstock Lode silver ore discovery in Nevada. Keith went to Munich to learn figure and portrait painting, feeling that a market for portraits would survive even the leanest of economic downturns. He also sought out new markets for his paintings, linking up with Chicago architect Daniel Burnham, who in 1888 gave a successful exhibition of Keith landscapes at the Rookery. One of the visitors to this Chicago show was George Inness (1825–1894), then at the peak of his fame as a painter of Barbizon-derived landscapes. Inness was impressed to find another landscape artist working in this style, and when he traveled to San Francisco in 1891, immediately connected with Keith. Interviewed by the local papers, Inness praised Keith, saying that if the locals understood what a great man he was, they would fall on their knees every time Keith passed them on the street. Inness’ opinions legitimized Keith’s Barbizon-style landscapes in the eyes of San Francisco collectors, and right after Inness’ departure for New York, Keith received many opulent commissions for dark paintings of oak trees and grazing cattle in California landscapes.

This resurgence earned Keith an exhibition at New York’s Macbeth gallery in 1893. Critics from the New York Times and New York Tribune praised the show in somewhat cautious terms, not sure whether the Far West, recently considered the frontier, could produce art of significant merit. In the same year, the jury for the art department of Chicago’s World Columbian Exposition originally admitted only two California paintings to the American galleries, leading to a tirade in a local newspaper by Keith: “The people in the East have an idea...that the productions of the Western states must all be crude.” As a result, Keith’s paintings were generously displayed in the art galleries of the California Building, where they received critical acclaim, and one of his paintings was later accepted in the American display.

|

| Fig. 7: William Keith (1838–1911) Secluded Grove, 1898 Oil on canvas, 12-1/4 x 16-1/4 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., college purchase |

|

| Fig. 8: William Keith (1838–1911) Evening Glow, 1891 Oil on panel, 23-3/4 x 28-1/4 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Celia Tobin Clark |

All through the nineties, Keith reigned as the leading landscape painter in San Francisco. After his death in 1894, Inness’ fame and prestige increased, and Keith’s reputation rose on the Inness tide. Increasingly, patronage of Keith’s paintings came from such Eastern collectors as Isaac Seligman, Jacob Schiff, and Edward Harriman. The high point of “Keithmania,” as it was termed, came in 1905 when New York architect Charles McKim visited Keith’s studio and bought eleven Keith paintings in the Barbizon mode (Fig. 9) for the then-astronomical figure of $15,000. McKim was quoted as marveling to a friend: “I was amazed and puzzled, for I observed pictures that at the first cursory glance suggested Daubigny and Corot and Millet and other acknowledged great masters of the poetic moods in landscape painting. But none of [Keith’s] pictures were in the slightest degree copies of those famous artists. A new master had arisen.... Such perfect and admirable work!”

In April 1907, New York’s Macbeth Gallery gave Keith another one-man show, but the New-York Daily Tribune’s art critic signaled the change in tastes when he noted, “Mr. Keith is faithful to a tradition that, if not precisely displaced by that of the votaries of sunshine [Impressionists], nevertheless sometimes seems to-day a little old fashioned.”

After Keith’s death in 1911, his reputation held steady for a few years. In April 1916, his son Charles held an auction of his paintings in New York City that netted over $30,000, thought to be “almost a record sale” by the New York Times critic. But over the next decade, Keith more or less disappeared from view. In 1929, when Keith’s niece Elizabeth Pond went looking for Keith paintings donated during his lifetime to the University of California in Berkeley, she found that they had been put in storage or hung in bureaucratic offices.

This trend continued. In the 1960s, when Stanford University Museum decided to upgrade its collection, they traded a six by ten foot Keith landscape and a Yosemite painting by Thomas Hill to the Oakland Museum for an unsigned old master painting attributed to Gaspard Dughet (1615–1675). At the last minute, Oakland was asked for $5,000 in cash to seal the deal.

|

| Fig. 9: William Keith (1838–1911) Grand Forest Interior, ca. 1900s Oil on canvas, 24-1/4 x 36-1/4 inches Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, Calif., gift of Mr. and Mrs. Albert T. Shine Jr. |

At the time, the Oakland Museum was becoming a center for the rediscovery of early California art, assembling the largest group of William Keith paintings anywhere. More recently, the museum has apparently changed its philosophy, and not one Keith landscape is currently on view in their galleries.

Over the last fifty years, although the great Eastern artists of the Hudson River School and Barbizon periods have undergone a significant re-appreciation, no such attention has been paid to the great California artists. Major California institutions have shown little interest in this area, and so it has fallen to energetic smaller museums like the Hearst Art Gallery at Saint Mary’s College to uphold the great art heritage of early California.

|

The Comprehensive Keith: A Centennial Tribute is on view at the Hearst Art Gallery, Saint Mary’s College, Moraga, California, through December 18, 2011. The refurbished Keith Gallery reopens on February 5, 2012. For information call 925.631.4379, or visit www.stmarys-ca.edu.

Alfred C. Harrison, Jr. is scholar of California artists and president of North Point Gallery, San Francisco, California.

This article was originally published in the Autumn/Winter 2011 issue of Antiques & Fine Art magazine, a fully digitized version of which is available at www.afamag.com. AFA is affiliated with Incollect.com.

|